The Occasional Journal

Love Feminisms

November 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton -

Feminisms in Contemporary Art Project Spaces

Kari Schmidt -

Considering Merata Mita’s Legacy

Chloe Cull -

Armour. Armor. Amor. More.

Zoe Crook -

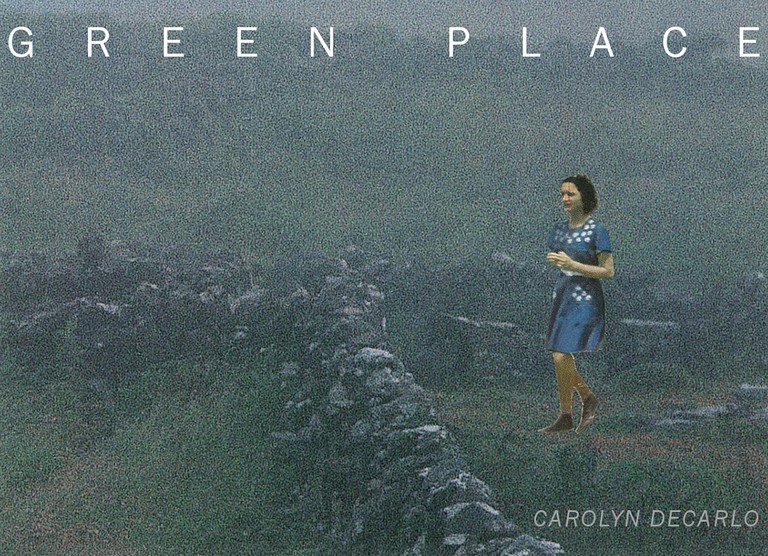

Green Place

Carolyn DeCarlo -

This mud body

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Body Language

Lana Lopesi, Louisa Afoa -

CONVERSATION

Creek Waddington, Sian Torrington -

Bloody Women Artists

Ruth Green-Cole -

the blue between me and you

Jo Bragg -

Urban Form and the Gendered Lens

Rosie Evans -

A guide

Rachel O’Neill -

Gender and the ANZAC Biscuit

Lindsay Neill -

Recovering Pieces: Finding an early history of women and photography in New Zealand

Lissa Mitchell

Green Place

Carolyn DeCarlo

—

© Carolyn DeCarlo

Origin Story

The world is a skull

spinning on a wheel.

Pull off the wheel and

hold it above your head.

Offer it as a token

to the guardian at the gate,

the one who will usher you

into Valhalla

I live

I die

I live again.

But we know the truth.

Who killed the world?

The world is not a skull

spinning on a wheel,

it is a Green Place,

it is an origin story

as old as the gods

carried over on a seed.

Aituā

The King is the root of it all —

one man, the silence, and all that power.

Powder his face and comb his hair,

adorn him in trinkets of glory.

Swaddle him in blankets, or better,

make him shine like the finish

on a 1959 Cadillac Coup de Ville—

Take that away,

and he’s just a boy in a robe.

Mote Wāhine

He tau mote wāhine,

it is a year for the female.

Tāwhiao quoted the whakataukī

after she killed her dogs for him.

A chivalrous act—

a sacrifice for the greater good.

One year for the woman,

but only after an expense had been paid.

That is the limitation of gratitude,

a worth summed up

in hours and days.

The years stretch before them

and only one declared their own.

If you were born to breed,

where do you go when that time is up?

What do you do with the remainder?

Raise wild dogs,

chase them around the Wasteland,

let them call you whaea

when no one is listening

except for the wind

and the desert

and the clouds racing toward you on the horizon.

FURIOSA

Pūrākau

This is my mythology:

bunched linen

tucked into three straps,

summed up in a choice

of costuming.

Where is my hapū?

I am pregnant with dread,

the Wasteland is unkind

and my sisters, my taina—

my tamariki whāngai.

This is my mythology:

a bundle of cloth

across my chest,

and the Immortan.

Kainga

Dreams of the Green Place,

heady and wild,

when my body was whole—

my arms so long they touched the sun.

Whaea, you said, meaning

mother of myself

and mother of my initiation.

What kind of dream is this?

7000 days, a lifetime—

a place of past,

a place of memory

like a library—

an erasure:

a swipe of grease

across the forehead

and she is gone

in three days,

she is gone to the Green Place.

Furiosa’s Mihi

I am one of the Vuvalini,

of the Many Mothers.

My initiate mother was K.T. Concannon.

I am the daughter of Mary Jo Bassa.

My clan was Swaddle Dog.

Twilight of the Gods

In the Green Place,

you watch the unnamed one

pour through the last of the bullets,

the anti-seed—

plant one and watch the thing die

and wait for the last

to take hold

but he stops short.

Hands the rifle to you.

Holds his breath

as you balance it

on his shoulder.

A voice in your head says,

Put the crosshairs on her nose

and you

Steady,

Take aim,

Fire,

watch as it catches,

blinding its maker,

the tiller of anti-seed.

I am the scales of justice,

the Bullet Farmer roars—

not as loudly as you will,

consumed in the no-home,

in the loss of redemption.

If his arms are the scales,

the balance is in your favor.

Only fair:

he’s lost his eyes—

yours are about to be opened.

Blood Bag

In a quiet room somewhere,

maybe in Idaho,

you are locking eyes

over frosted beers.

There is a lot of wood paneling

and static electricity.

This could be Road House

on a slow night,

or a version of Dirty Dancing

where Patrick Swayze played Baby,

Jennifer Grey lifting him over her head.

I am the one who runs

from both the living and the dead.

Give me a cliché that is not suited

for a man and a woman in love.

Give me a word for brother-love

that is not bound to Patriots, to Black Hawks,

to men for others.

Give me a way to trace the shape

of a relationship formed from mutual distrust—

not so unusual, so what is it?

What is in a name?

Or, better—

what’s in an un-name?

The desire to remain unnamed.

The story goes:

when you give up your name,

you give up a piece of yourself.

Eventually, this is worth doing.

Imperator

I am tuakana.

My existence is dependent

upon the other, the taina—

the bundle of limbs

and wide eyes

under my feet.

How many women have you served

in your lifetime?

How many women

brought freely into the desert?

1-1-2-1. Red. Black. Go.

I would give my life for them

a thousand times.

FIVE WIVES

Anghared

Much loved one,

and so she is—

the Splendid.

In fantasy,

she is the goddess of birth,

bearer of wisdom,

keeper of the seeds.

In truth,

she has been a witch,

a miner’s daughter,

a novelist.

She has lived mostly

in a country whose name

confounds the world so much

they changed it.

Instead, she names it

Crescent Grove,

Corellon’s palace,

The Citadel.

They think she carries

a perfect thing inside of her—

a safeguard,

a talisman.

But it is anti-seed

and it is set for destruction.

A Dag—

not fit to do

what?

Kept pure,

locked in

by a belt.

She is chaste,

what is that?

The introduction

of a concept

by man,

pure of heart

and spirit,

of course.

The notion of

illegitimacy

and the law’s

condemnation of it.

Pregnancy hapū

creates property tamariki—

this is not tradition.

Capable

She finds him,

curled up like a koru

in the back of the War Rig.

Dependable red-head,

I can do it,

she says to Furiosa—

I can do it.

Makes you wonder

if he could have done it

without her.

Hands cupped,

they form a new thing,

hope—

in the future,

in each other.

Inu

Glasses clink around the circle

and a pair of roving eyes catches yours,

glazed but serious, earnest—

unsettling in their co-operation

with the brain.

I propose a toast,

only appropriate at weddings,

occasions of great importance,

not here in the Wasteland,

a circle of five women dressed in white.

Toast carries the bullets,

counts them and remembers to subtract

four left, three, two—

she, too, is capable,

confident in her knowledge.

She knows things

before they happen?

No, but—about them happening.

She is ready for them.

Fragile

We don’t know much about this girl,

do we?

She could be anyone.

A catalogue of facts:

She’s the youngest,

She’s the only one who asks to go back.

She’s the one who’s given up as bait.

She survives.

Another fact:

Girls like Cheedo exist.

Is it an erasure

to ignore this,

to invalidate this response?

A person hides themselves,

a person fears what isn’t known,

a person wants to be needed,

a person recognises:

being found will be hard,

staying lost could be harder.

A person wants to stay alive.

When you’re the prized,

you’re given privilege.

In the beginning,

there may be room for hope.

She isn’t the role model —

she is a station of the self.

© Carolyn DeCarlo

Keeper of the Seeds

Kuia carries the seeds

in a leather carpet bag

she holds tucked to herself

for luck.

She counts them out:

One for the men

we buried in the sand,

Two for the mothers

who carried our land,

Three for the Green Place

where we will all go,

Four for the crows,

who stole our home.

When Papatūānuku ate the seeds,

the Earth was born.

Give me just one seed

and I can grow a world inside me,

whenua slipping out

between my legs,

placenta unfurling into mamaku.

Whānau

There is no property in children,

Miss Giddy used to say,

no owning a woman or a child.

Having a baby in the Wasteland is hard work,

but raising a child in the Citadel is impossible.

If you deliver your child to the whānau

your child will bring good fortune.

Whāngai children are special,

held in high regard, the chosen ones

of many homes, but still one whānau.

On Being Immortal

White powder blown

from the mouths of slaves

onto fissured skin the shade

of old garlic cloves

to keep away pain.

His power was sick,

all boils and cancer

obscured, and yet

laid bare by Plexiglas,

the hardened muscles

and medals molded,

a false layer

lacquered over

his deflated skin

for luck, for trust, for might.

They say his eyes were red—

red as pricks,

red as the river flowed

when his mask was torn away.

What kind of infant wears a mask?

You know the answer to this.

You were an infant once yourself,

in the Wasteland.

History Woman

In the end, it is not a mask

that separates you,

it is a series of scryings,

a map drawn out across your face.

She is kuia, and you,

you are kuia, too.

Beware, Immortan.

When you gave them History Woman

you gave them power—

knowledge wasn’t ever yours to give.

Kōpū

He says, I myself

will carry you

to the gates of Valhalla,

but he never carried you.

He’s never carried anything

human inside of him, not once.

Sooner or later,

someone pushes back.

Carry something long enough

and it will kick a hole in you.

VALKYRIE

Valkyrie

What do you know of the North?

Your bones are bound to the desert,

bait for the battlers,

the lone wolves, the profiteers

coming to stake their claim

on the Many Mothers—

but they will fail

many times over.

Your keening is louder

than even the War Boys’

cracked lips

on their chrome-coated

journey to Valhalla.

You thread through the dusty sky

covered only by your own skin,

searching for worthy ones.

If only they knew—

you were the one with the power,

you were the last of your kind

and when they managed to kill you

no one would be carrying them

to the gates of Valhalla,

least of all Joe

(not immortal at all,

just a dried up old war man,

worn as the husk of an old garlic clove,

pumped full of air).

At least this way,

you’ll live and die

without bearing their mead

in the hall of the slain.

Dust and sand have borne you

and your sisters far away

from the grasping hands of Odin,

and that is a small seed of comfort

for you to carry, perhaps.

Sessrúmnir

Valkyrie, are you

one of many? Or,

are you she—

the chosen one, Freyja,

ruler of Fólkvangr?

Oh, go on, show us your cloak

of falcon’s feathers,

your chariot of cats,

your red-gold tears.

Let us go to your ship now,

the great hall that bears

your warriors upon the sea,

and take in the waters.

It is time to bring them

freshwater to drink.

The many Wretched

are in need of it—

theirs is a big thirst,

and it is long

since it has last been sated.

Freyja

How do you choose

your beautiful, fallen warriors?

Are they the ones with the tears,

the ones who broke hearts,

the ones with dimples and curls

or chiseled jaws,

the valiant ones,

the hardest to fall,

or—

No.

The most disgusting men,

you bear to your breast

with a sly grin,

their fingertips just shy of Odin’s clasp,

sweaty dream-cape of Valhalla

ripped to shreds

by a woman

riding a chariot

led by cats.

The Bright-Eyed One

Set your sights on the skies—

not back to the Green Place

but rather up, to the black dots

glimmering at its edge.

They’re drawing closer,

feathers dripping corpse-blood,

good fortune for the Vuvalini,

the Many Mothers living in the no-home.

There is not much choice

between a salt field and a swamp.

Take up the wisdom of the raven,

it’s pitched deeper even than the cackling

of the crows who stalk the swamplands

and pool at the feet of the stilt-walkers,

damp feathers tangling with the shrouds

until their crafty bodies are lifted up

and carried across the night.

The ravens are coming

with beaks all gory, at break of morning

warning of battles waged and lost

far back along the trail beyond the Green Place,

beyond the lightning storms, in the belly of the Wasteland.

And you, Tūī, white-throated raven,

the bright-eyed one, where will you go?

West to the salt flats, the dried up old whale-road,

or back along the desert hills to the Citadel

dripping emerald from its haunches?

No, Tūī, go North, Tūī.

Hide your shimmering plumage

among your blood-soaked friends,

chase the tail of the sun

until it leads you to Valhalla.

Aotearoa

In truth, there were thirteen maidens,

a perfect snatch of fragile things

carried in a crate by Odin himself.

The hens bore them all out one night,

a miracle when their shells held.

Odin lined them up and named them,

stroked them thoughtfully with his thumbs

and tried to keep them safe—

but he was only a man.

Eventually, in a night-sweat,

dreaming he was someone else

Odin cracked his lips and

Mist slipped her hand between them,

shouldering her way out,

a long white cloud forming on the horizon.

Acknowledgements

Lines from Mad Max: Fury Road were used in Origin Story, Furiosa’s Mihi, Twilight of the Gods, Blood Bag, Imperator, Capable and Kōpū, and often appear in italics.

The whakataukī quoted in Mote Wāhine appears in full in “The Negation of Powerlessness: Maori Feminism, A Perspective” by Ripeka Evans.

The first and last lines of Whānau are quoted from “Maori Women: Caught in the Contradictions of a Colonised Reality” by Annie Mikaere.

The Bright-Eyed One includes a quote from the fragmentary skaldic poem Hrafnsmál, generally attributed to Thorbjörn Hornklofi.

The work of several Māori feminist scholars proved invaluable in my research leading up to the creation of this series, including Annie Mikaere, Ripeka Evans, Mei Winitana and Paulé Aroha Ruwhiu.

Thanks to the NZETC at the Victoria University of Wellington Library for providing electronic access to the full text of Takitimu by Tiaki Hikawera Mitira (aka J.H. Mitchell). Thanks to Te Papa, Te Ara, Te Tāhuhu o te Mātauranga (Ministry of Education), Te Minitatanga mō ngā Wāhine (Ministry for Women), and the Mad Max Wiki for providing the quick facts.

Threading together the mythography of Mad Max with study of pre-colonial Māori life and myths led me down avenues I never expected; in particular, the Valkyrie series, which brought in elements of Norse mythology through the Poetic Edda and skaldic poetry. Thank you to Ann Shelton and Alice Tappenden at Enjoy Journal for giving me a platform to explore this. What I thought would be a straightforward series of poems about Mad Max: Fury Road became something far more web-like.

Thank you, George Miller, for not being an awful director, and for choosing to consult with Eve Ensler. The genre of the action film still has a long way to go, but Fury Road felt like a win.

A final thanks to my friends in Wellington and on Twitter who put up with all my chattering aboutMad Max over the past several months, and to my partner and best friend Jackson Nieuwland for being my sounding board for everything.

Bibliography

Evans, Ripeka. “The negation of powerlessness: Maori feminism, a perspective.” Hecate 20.2 (1994): 53.

Hornklofi, Thorbjörn. “Hrafnsmál.” In Old Norse Poems: The Most Important Non-skaldic Verse Not Included in the Poetic Edda, ed. Lee M. Hollander, 56-62. New York: Columbia University Press, 1936. Accessed August 11, 2015. http://sacred-texts.com/neu/onp/onp11.htm.

Mikaere, Anne. “Maori women: Caught in the contradictions of a colonised reality.” Waikato L. Rev. 2 (1994): 125. Accessed August 4, 2015. http://www.waikato.ac.nz/law/research/waikato_law_review/volume_2_1994/7.

Miller, George, Brendan McCarthy, and Nico Lathouris. Mad Max: Fury Road. Film. Directed by George Miller. Los Angeles, CA: Warner Bros., 2015.

Mitira, Tiaki Hikawera. Takitimu. Wellington: Reed Publishing, 1972. Accessed August 12, 2015. http://nzetc.victoria.ac.nz/tm/scholarly/tei-MitTaki-t1-front-d1.html.

Ruwhiu, Paulé Aroha. “Ka haere tonu te mana o ngā wahine Māori: Māori women as protectors of te ao Māori knowledge.” Master in Social Work diss., Massey University, 2009. Accessed August 12, 2015. doi:10179/1793.

Wintana, Mei. “Contemporary perceptions of mana wahine Māori in Australia: A diasporic discussion.” MAI Review 3.4 (2008): 1-8. Accessed August 10, 2015. http://www.review.mai.ac.nz/index.php/MR/article/viewFile/179/188.

About the Author

Carolyn DeCarlo is an American writer living in Wellington, where she runs the reading collectiveFood Court. She holds an MFA in creative writing from the University of Maryland, College Park. She has written a chapbook, Strawberry Hill (Pangur Ban Party 2013) and co-authored two chapbooks with Jackson Nieuwland: Twilight Zone (NAP 2013) and Bound: An Ode to Falling in Love (Compound Press 2014), winner of Auckland Zinefest’s Best Literary Zine of 2015. You can find some of her writing published or forthcoming from PANK, The Fanzine, Heavy Feather Review, West Wind Review, and Sweet Mammalian.