The Occasional Journal

Love Feminisms

November 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton -

Feminisms in Contemporary Art Project Spaces

Kari Schmidt -

Considering Merata Mita’s Legacy

Chloe Cull -

Armour. Armor. Amor. More.

Zoe Crook -

Green Place

Carolyn DeCarlo -

This mud body

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Body Language

Lana Lopesi, Louisa Afoa -

CONVERSATION

Creek Waddington, Sian Torrington -

Bloody Women Artists

Ruth Green-Cole -

the blue between me and you

Jo Bragg -

Urban Form and the Gendered Lens

Rosie Evans -

A guide

Rachel O’Neill -

Gender and the ANZAC Biscuit

Lindsay Neill -

Recovering Pieces: Finding an early history of women and photography in New Zealand

Lissa Mitchell

Feminisms in Contemporary Art Project Spaces

Kari Schmidt

‘Feminisms’ is a notion little explored by art project spaces throughout New Zealand. Although feminism and related issues have been touched upon, there is both a distinct aversion to the word ‘feminism’ and a lack of complexity in its representation.

I intend to use a quote from the callout for this journal as a provocation to examine contemporary arts practice in art project spaces as it relates to feminism:

What does it mean to be a feminist on the marae? What does feminism mean to a refugee from a culture where gender expectations differ from those of Aotearoa New Zealand? What does it mean to be a feminist when you shift between genders? What does feminism mean to you when you’re a mother who can’t earn enough to pay childcare? What does it mean to be a feminist when you’re a father and people talk about you babysitting your children as though you’re the backup parent? What does it mean to be a feminist when you’re deeply involved in a patriarchal religious belief system?1

This essay intends to address the extent to which questions such as this have been explored within artist project spaces and, more generally, the manner in which feminism has been represented in these contexts, with reference to the archives of Enjoy Gallery in Wellington, Blue Oyster Gallery in Dunedin and Artspace in Auckland. These kinds of questions are associated with a more complex feminism that embodies a far broader range of perspectives and experiences—hence the use of the plural term ‘feminisms’. Implicit in the term is the idea of intersectionality—a feminism which recognises the overlap between different systems of oppression. For example, while all women have to navigate living in a patriarchy, women who are, for example, Māori, Asian or African-American, face their own set of challenges, which are defined by race. In this way, the term ‘feminisms’ recognises that no single feminist paradigm or perspective exists and attempts to address the intersection between feminism and issues of class, race and gender, as well as economics, culture and religion. Hence Māori feminism, eco-feminism, postcolonial feminism, Third-world feminism, Islamic feminism, transfeminism and socialist feminism, all of which are included in this term. The term ‘feminisms’ recognises that feminism can mean wildly different things to different people, based on their various characteristics and experiences. It is extremely important that contemporary art in project spaces engages with this term, given that ‘feminisms’ recognises the complexity and diversity of the issues at stake in feminism today, rather than confining feminism to the previously dominant liberal, Western, middle-class model.

Through examining these three spaces I hope to provide an adequate spread of the kind of work produced in some of the most well-known art project spaces throughout New Zealand and to thus contextualise Enjoy’s decision to curate a journal and exhibition on the theme of feminisms in 2015.

Feminisms at Enjoy Gallery, Blue Oyster Project Space and Artspace

Feminism and issues relating to it have featured in various ways throughout the history of these three project spaces. For the most part, artists have conducted a relatively subtle commentary on the question of feminism and related issues such as gender, sexuality and labour—the word ‘feminism’, for instance, has never been explicitly used in relation to any exhibition description on Enjoy’s website (the descriptions accompanying all of the archived shows within Enjoy’s history).

The relationship between women and craft or domestic labour has been considered in a number of exhibitions. In Te Whare Pora (2013, Enjoy Gallery)2 by the Mata Aho Collective, the fibre arts, and weaving in particular, were explicitly considered feminine under the atua of Te Whare Pora, Hineteiwaiwa (the Māori God in charge of the feminine arts), with the exhibition featuring a giant mink blanket in the Enjoy space (fig. 1 and 2), and a video showing the all-female artists working together to produce the blanket. In Cottage Industry (1997, Artspace)3 Ani O’Neill used Cook Islands art practices such as tivaevae, weaving, plaiting and sewing, which are traditionally seen as feminine, by presenting a series of crocheted discs. Recontextualised, these works verged on the abstract, reminiscent of Jasper Johns’ target paintings and Julian Dashper’s drum heads—thus problematising the low/high art distinction associated with craft and women’s work generally. Similarly, Ruth Buchanan and Georgie Hill in Decoration and Crime (2001, Enjoy Gallery) used materials associated with “the traditional position of women as homemaker/house padder”4 in emphasising the skill involved in craft. Tracey Cockburn’s Unearthed (2003, Blue Oyster) produced delicate works referencing the craft of pinning, in an examination of the everyday history of a site in Hobart, “in order to link notions of the domestic, women’s work or craft making as well as the preoccupation many contemporary women artists have with these.”5 Although none of these shows were explicitly described as feminist, they engaged with the intersection between labour, economics and feminism through exhibiting and engaging in the process of craft. For instance, the very fact of these works being exhibited in a gallery context served to elevate the status of craft, a traditionally feminine practice which historically has been characterised as purely utilitarian within the patriarchal art world. Similarly, in her work O’Neill blurred the line between ‘high’ and ‘low’ art, through using craft to present artworks that bear a striking similarity to famous abstract paintings. In this way, artworks concerned with the traditionally feminine practices of craft and domestic labour can be said to have had a distinctly feminist undertone. Te Whare Pora was also to some extent intersectional in nature, given that it considered craft practice from a Māori perspective— although again there was no explicit commentary on feminism or the outlook of Māori women as Māori women, per se.

Fig 1. Mata Aho Collective, Te Whare Pora, mink blankets, installation view. 2013 © Enjoy Public Art Gallery

Fig 2. Mata Aho Collective, Te Whare Pora, video, dimensions variable. 2013 © Enjoy Public Art Gallery

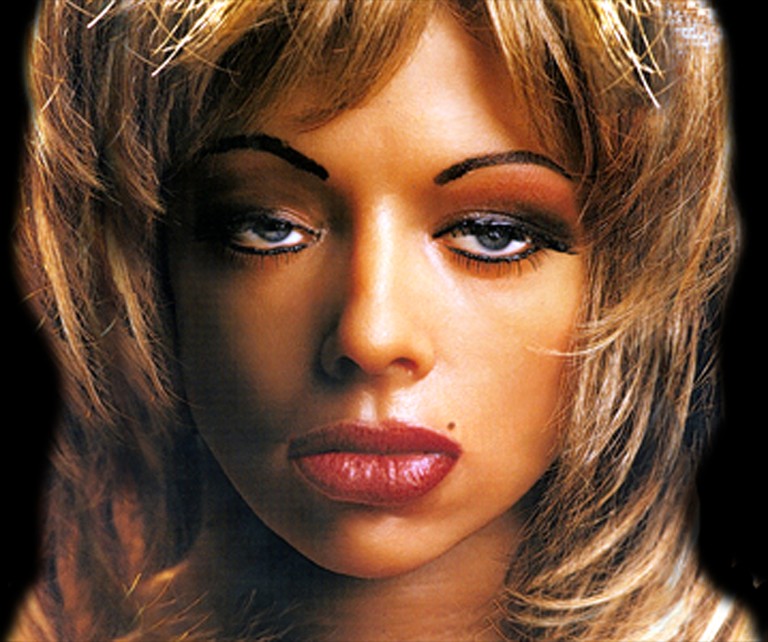

Gender has also been a reoccurring theme, as in Mark Harvey’s show Home Helper (2003, Enjoy Gallery),6 where the artist re-enacted the stereotype of the DIY male, implicitly commenting on common masculine labels. Similarly, the Kingpins in Curiosity Kills the Gap (2003, Artspace) consisted of four women dressed as men, acting to perform masculine stereotypes.7 Sandy Gibbs in Sometimes a kiss is… not just a kiss (2006, Enjoy Gallery)8 also commented on issues of gender as an ambiguous construct (for example, through exploring the persona of female bodybuilder, Bev Francis), as did Angela Lyon in double (2007, Blue Oyster)9 when she played with gender constructs in modelling herself after Elvis. et al. also considered Duchamp’s use of the feminine persona Rrose Selavy in simultaneous invalidations: second attempt (2001, Artspace).10 The nature of experience as gendered has also been considered, as when Justine Walker represented “the woman alone”11 in her self-portraits (2007, Blue Oyster), or when Max Oettli explored “the redundancy of men in the modern world”12 in MEN (2008, Blue Oyster). Similarly, Justine Kurland constructed an “all-girl-world as a form of Utopia”13 in her self-titled exhibition (2002, Artspace)—an imaginary world of teenage girls in largely natural environments, emphasising their “empowerment, independence, camaraderie and intimacy.”14 In other words, a place for women to be outside of the presence of men. Jodi Stuart problematised the relationship between beauty and femininity in her contribution to Flesh and Fruity (2001, Artspace), where she “[scrambled] feminist concerns with her barely interactive video-game Leisureware. Barbie trashes the room, and anything and everything that comes her way, punctuated by bum-wiggles”15 (fig. 3 and fig. 4). Hito Steyerl similarly touched upon the intersection between feminism and sexuality by featuring the Japanese bondage industry in her exhibition After the Crash (2009, Artspace),16 which also dealt more generally with issues of globalisation, post-colonialism and inequality. In this way, gender as a construct and the manner in which it impacts upon men and women has been examined, although again no works have approached this from an actively feminist standpoint, or from an explicitly transgender standpoint—another perspective which the term ‘feminisms’ aims to recognise.

Fig 3. Jodi Stuart, Leisureware, video, dimensions variable, 2001. © Artspace NZ

Fig 4. Jodi Stuart, Leisureware, video, dimensions variable, 2001. © Artspace NZ

Various works, while not engaging directly with feminist issues, have aimed to provide opportunities for the voices and perspectives of women to be heard. The all-female exhibition Excess Baggage (2015, Blue Oyster Gallery), for example, “[explored and tested] notions of displacement, challenge and endurance that are often the vector that shapes and forges the life of any given woman around the world.”17 Work by Elena Kovylina in this exhibition considered the female experience of managing the home (fig. 5), as well as other issues associated with globalisation such as migration, nomadism and a yearning for home. Although Excess Baggage was relatively broad in scope and not pointedly about feminism per se, it still facilitated the expression of women and their perspectives. Similarly, Marysia Lewandowska’s RE-NEGOTIATION (2015, Artspace) included her open-source project Women’s Audio Archive (1984-1990), which included various recordings of events, seminars, and talks from 1984-1990, a time “dominated by academics and artists close to October magazine and by feminist gatherings.”18 Such works take a kind of ‘post-feminist’ approach, aspiring to advance the position of women and make their voices louder, without overtly subscribing to the doctrine of feminism in an essentialist sense.

Fig 5. Elena Kovylina, Caryatid, digital video, sound 4.55, wall mounted, 2012. © Blue Oyster Gallery

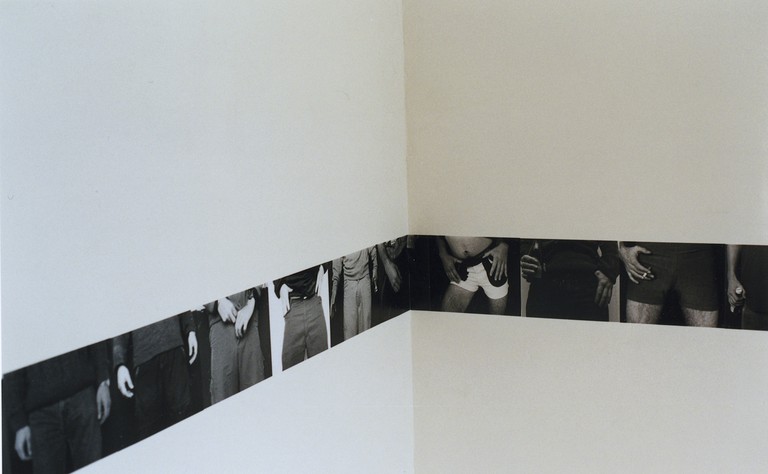

Conversely, a number of shows have explored feminist themes more overtly. Avangard/PinkPunk in The Bomb (2005, Enjoy Gallery) performed ‘Fair Deal’ in Wellington, which considered “women’s role as pleasure accessory to the powerful players of business and politics.”19 Similarly, Amanda Ra in Grand Prix (2000, Enjoy Gallery)20 aimed to subvert the male gaze, turning it back onto men through presenting a series of images of men, all of which were taken at crotch height (fig. 6).

Fig 6. Amanda Ra, Grand Prix, detail, 2000. © Enjoy Public Art Gallery

Tracey Moffatt took a similar approach in Heaven (2000, Artspace)21, where she took grainy, voyeuristic videos of male surfers at Bondi beach. Phoebe Lysbeth Kay Mackenzie similarly considered the nature of the male gaze and street violence against women in When I Grow Up,22 which featured an intoxicated young women walking through town at night in high heels, being verbally accosted by young men (fig. 7 and fig. 8). In Fox Rox (2002, Blue Oyster),23 A.D. Shierning utilised a mixed-media installation in order to “[explore] the implications of a feminist revival”24 through presenting a series of patches and leather jackets reminiscent of gangs, coupled with insignia evocative of ‘girl-power’ (fig. 9 and fig. 10). And Fiona Jack (in post-Office, 2010, Artspace) worked off an 1893 photograph of women voting in New Zealand, thereby speaking to “women, art, labour and the contemporary state of feminism.”25

Fig 7. Phoebe Lysbeth Kay Mackenzie, When I Grow Up: Walk, looped video, glass, full wall projection, 2012. © Blue Oyster Gallery

Fig 8. Phoebe Lysbeth Kay Mackenzie, When I Grow Up: Walk, looped video, glass, full wall projection, 2012. © Blue Oyster Gallery

Fig 9. A.D. Schierning, Fox Rox, mixed media, 2002. © Blue Oyster Gallery

Fig 10. A.D. Schierning, Fox Rox, mixed media, 2002. © Blue Oyster Gallery

Such works have, however, largely interpreted feminism through a Western, middle-class paradigm. ‘Feminisms’ as a concept is never addressed explicitly, and there is little to no work on feminism as it relates to race, religion, the environment, transgender issues or economics. Even when ‘feminism’ is explicitly considered in an exhibition, a certain degree of hedging takes place, as in When I Grow Up: “The exhibition is not strictly feminist in nature. However, with an all-female group of artists and curator the nature of the works in the exhibition lend to a feminist interpretation.”26 Chantal Fraser’s recent exhibition, It’s incredible… It’s all ours (2015, Enjoy Gallery), did implicitly consider feminism from a colonial/race perspective. The title of the show refers to European colonialists—men such as Jack London and Bengt Daniellson—who travelled to the Pacific and conceptualised indigenous women as theirs for the taking. Fraser hung a variety of veils, hoods, petticoats, and other clothing in the space, referencing of the adornment of women in these contexts as well as in the West (fig. 11 and fig. 12). As the exhibition text states:

Via experiences of seduction and longing, the curiosities and romanticism of colonialism are considered in reference to the past and allude to consequences of colonialism from a female perspective.27

Fig 11. Chantal Fraser, It’s Incredible… It’s all ours, hand-sewn fabric, bead and sequins, instillation view. 2015. © Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

Fig 12. Chantal Fraser, It’s incredible… it’s all ours, hand-sewn fabric, bead and sequins, detail. 2015. © Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Image courtesy of Shaun Matthews.

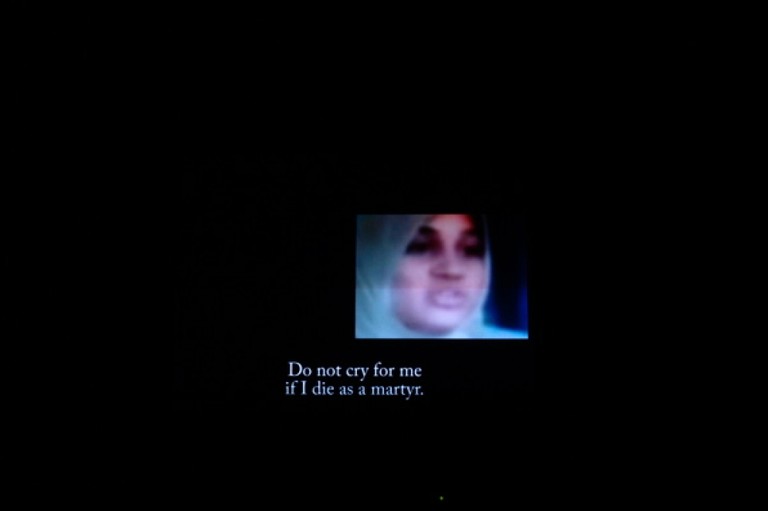

Similarly, Janna Todd in The youtube Criers (as part of the Blue Oyster 2008 Graduate Exhibition)28 featured a work exemplifying the extremes of Youtube—a woman crying because she has been called a ‘douche’ is contrasted with an Iraqi woman recounting her rape (fig. 13 and fig. 14). Todd’s work implicitly contrasted the experiences of Western and non-Western women, however, the exhibition and accompanying text for this work did not explicitly focus on feminism or feminisms, and instead emphasised the varying nature of what can be found on Youtube, asking “Does this phenomenon generalise our compassion? Does it drain compassion? Is it a natural progression? One thing is certain it exists!”29

Fig 13. Jenna Todd, The youtube Criers, digital video, full wall projection, 2007. © Blue Oyster Gallery

Fig 14. Jenna Todd, The youtube Criers, digital video, full wall projection, 2007. © Blue Oyster Gallery

As these examples evidence, a number of artists have touched on the concerns inherent in the term ‘feminisms’ within these contemporary art project spaces, through examining gender, considering the nature of female labour, craft and the domestic, or more overtly in tackling questions of the gaze, the commodification of women’s bodies, violence against women and feminism itself. However, the history as it is outlined here evidences a lack of engagement with intersectionality. Very few works touch upon the overlap between feminism and issues such as race, class, religion, colonialism and the environment. Similarly, we see a hesitation to engage in feminism directly—the word ‘feminism’ is barely ever used in relation to these artworks and again, feminism is not once named explicitly in the Enjoy archive to date. Despite the wealth of this area of enquiry, ‘feminisms’ has also never been explicitly addressed within an exhibition at Enjoy Gallery, Blue Oyster Gallery or Artspace. Associated with unfashionable ‘identity politics’ and considered a passé term in the wake of second wave feminism, artists and others working within the field have tended to take a post-feminist approach. And yet, it is undeniable that the inequality to which feminism first spoke continues to persist. Articulating feminism in the plural as ‘feminisms’ is in this respect a means of moving beyond this impasse, as the term broadens the scope of feminism without watering down its focus in the way that words such as ‘equalism’ or ‘humanism’ do.

Given that feminism has once again started to enter the public consciousness, it is highly apt for Enjoy to engage in the question of feminisms in 2015, especially given how politically and socially pressing feminism still is, and how much there is to explore in the pluralism, complexity and diversity that the term ‘feminisms’ encapsulates. Similarly, the exhibition accompanying this journal will be one of the first opportunities in the history of New Zealand art project spaces to see what an intersectional and explicitly feminist exhibition could look like.

About the author

Kari Schmidt is currently completing her Art History (Honours) degree at Victoria University. In 2015 she graduated from Otago University with an LLB (Hons) and BA in Art History. Her Law dissertation pertained to the impact of Copyright law on Appropriation Art. It won the NZIPA Loman Friedlander award and will be published in the New Zealand Intellectual Property Law Journal and the New Zealand Student’s Law Journal. She is Co-Founder, Co-Editor and Writer for Up and Adam, a blog by Victoria University art students on contemporary art in association with the Adam Art Gallery (upandadam.tumblr.com). She was also the 2015 recipient of the Chartwell Trust Art Writing Prize.

-

1.

Enjoy Gallery Trust, “Considering Feminisms in Aotearoa New Zealand: Two Projects: A Call for Exhibition and Journal Proposals”, accessed July 01, 2015, http://www.enjoy.org.nz/files/CalloutConsideringFeminisms.pdf

-

2.

“Te Whare Pora,” Enjoy Gallery Archive 2013, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, accessed June 10, 2015.

-

3.

“Cottage Industry,” Artspace Exhibtions 1997, Artspace NZ, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/1997/anioneill.asp

-

4.

“Decoration and Crime,” Enjoy Gallery Archive 2001, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, accessed June 10, 2015.

-

5.

“Unearthed,” Blue Oyster Archive 2003, Blue Oyster art project space , accessed June 29, 2015, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/tracey-cockburn/

-

6.

“Home Helper,” Enjoy Gallery Archive 2008, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, accessed June 31, 2015.

-

7.

“Curiosity Kills the Gap,” Artspace Exhibtions 2003, Artspace NZ, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2003/curiositykillsthegap.asp

-

8.

“Sometimes a kiss… is not just a kiss,” Enjoy Gallery Archive 2006, Enjoy Gallery, accessed 10 June 10, 2015.

-

9.

Angela Lyon, double, (Dunedin: Blue Oyster Gallery, 2007), Online PDF, accessed June 21, 2015, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/assets/PDFs/2007-PDFs/Double-2007-catalogue.pdf “double,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 21, 2015 http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/curated-by-ana-terry/

-

10.

“simultaneous invalidations: second attempt,” Artpsace Exhibtions 2001, Artspace NZ, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2001/etal.asp

-

11.

Justine Walker, double, (Dunedin: Blue Oyster Gallery, 2007), Online PDF, accessed June 21, 2015, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/assets/PDFs/2007-PDFs/Double-2007-catalogue.pdf , “double,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 21, 2015 http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/curated-by-ana-terry/

-

12.

“MEN,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 21, 2015, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/max-oettli/

-

13.

“Justine Kurland,” Artpsace Exhibtions 2001, Artspace NZ, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2002/justinekurland.asp

-

14.

Ibid.

-

15.

“Flesh and Fruity,” Artpsace Exhibtions 2001, Artspace NZ, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2001/fleshandfruity.asp

-

16.

“After the Crash,” Artpsace Exhibitions 2001, Artspace NZ, accessed June 21, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2009/hitosteyerl.asp

-

17.

“Excess Baggage,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 21, 2015, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/excess-baggage/

-

18.

“The project includes the participation of Judy Chicago, Mary Kelly, Barbara Kruger, Yvonne Rainer, Jo Spence, Nancy Spero, Jane Weinstock, and many others, in a variety of settings.” , “RE-NEGOTIATION”, Artspace NZ, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2015/

-

19.

“The Bomb,” Enjoy Gallery Archive 2005, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, accessed June 10, 2015.

-

20.

“Grand Prix,” Enjoy Gallery Archive 2005, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, accessed June 10, 2015.

-

21.

“’You could call Heaven a revenge film, but I would call it a comedy’, says Moffatt. ‘Most straight guys hate it. But I didn’t make it for men—I made it for all the women in the world who like to look.’”, “Heaven,” Artpsace Exhibitions 2000, accessed June 21, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2000/traceymoffatt.asp

-

22.

“When I Grow Up,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/when-i-grow-up/

-

23.

“Fox Rox,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 17, 2015, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/a-d-schierning/

-

24.

Ibid.

-

25.

“post-Office,” Artspace Exhibitions 2010, Artspace NZ, accessed June 21, 2015, http://www.artspace.org.nz/exhibitions/2010/postoffice.asp

-

26.

Ibid, n 22.

-

27.

“It’s incredible… It’s all ours,” Enjoy Gallery Archive 2015, Enjoy Public Art Gallery, accessed July 15, 2015.

-

28.

“2008 Graduate Exhibition,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 17, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/exhibitions/2008-graduate-exhibition/

-

29.

“2008 Graduate Exhibition,” Blue Oyster Archive 2007, Blue Oyster art project space, accessed June 17, http://www.blueoyster.org.nz/assets/PDFs/2008-PDFs/2008-Grad-Show.pdf