The Occasional Journal

The Dendromaniac

March 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton, Jessica Hubbard -

For the trees

Rachel Buchanan -

dwelling trees, tree dwellings

Xin Cheng -

Axis Mundi: Long Live the Tree of Life

Prudence Gibson, Tessa Laird -

Forest satyagraha

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Garden City

Holly Best -

Accentuated Breath

Clare Hartley McLean -

On the portraiture of mushrooms

Creek Waddington -

Shade

Andrea Gardner -

bigwoods

Emil McAvoy -

Regan Gentry: Transformer and Master of Time

Sharon Taylor-Offord -

Colonisation versus conservation: a colonial view

Rebecca Rice -

Tae

Bridget Reweti -

The Framing of the Earth

Richard Shepherd -

Wildness in the Garden of Empire

Shaun Matthews -

In search of unknown vandals

Bronwyn Holloway-Smith, Thomasin Sleigh -

Bo.tan.i.cal: from the Greek

Jessica Hubbard -

The Tree as Traveller: Sakura in space, kōwhai in Chelsea, and the oldest pohutukawa in Spain

Emma Ng -

Seeing the wood and the trees: a complicating history of Hitler’s Oaks

Ann Shelton -

Conversations with Cripplewood

Cat Auburn -

Out of the Woods: The Return of Twin Peaks

Alice Tappenden, Matt Plummer -

The conceptual, the pastoral, and the plainly freakish (or, some of my favourite artworks are trees…)

Martin Patrick -

This is a femme slam.

Sian Torrington -

Explorations

Christian Nyampeta -

Works from the series An Ethnography on Gardening, 2006-2008

Raul Ortega Ayala -

Bent

Jonathan Kennett, Mary Macpherson -

One Shining Gum / Savia Brillante

Christina Barton, Maddie Leach, Zara Stanhope -

Acknowledgments

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton

Colonisation versus conservation: a colonial view

Rebecca Rice

New Zealand, entirely unsettled – New Zealand in its old wild state – might be very much more valuable, clothed with forest, than New Zealand denuded of forest and covered with public works, constructed at enormous cost and with enormous labour.1

Remarkably, these words were spoken 140 years ago, by the Premier of New Zealand, Julius Vogel, in response to the second reading of the New Zealand Forests Bill. The Bill proposed that the government legislate for proactive conservation of the colony’s forests and was ardently supported by Vogel in a 16,000 word speech. This seemed in stark contrast to his ambitions as Premier; for Vogel was responsible for pushing a new wave of immigration during the 1870s as well as dramatically expanding public works, particularly the building of railroad and telegraph networks throughout New Zealand.

This was not, however, the first time concerns about the deforestation of New Zealand were aired. In the 1860s, Thomas Potts and William Thomas Locke Travers, lawyer, politician, photographer and conservationist, drew attention to the negative consequences of deforestation on New Zealand’s ecology. Later in the century, several artists joined the conversation, advocating for the preservation of the New Zealand bush.

This article seeks to situate artist’s responses to the New Zealand landscape in relation to an emergent discourse of conservationism, exploring what their pictures reveal of attitudes towards the ‘bush’ and the purposes those images served.

Axes in art

![William Strutt, Mangarie [Mangaire], Taranaki, New Zealand, 1856, pen and wash, National Library of Australia: nla.pic-an3240357](/media/cache/42/30/4230f938d50a60fb5c4ff73e7c3adb1d.jpg)

William Strutt, Mangarie [Mangaire], Taranaki, New Zealand, 1856, pen and wash, National Library of Australia: nla.pic-an3240357

Once you start looking, it is hard not to notice the frequency with which axes and tree-stumps feature in colonial depictions of the New Zealand landscape, at least in those which offer some record of daily life, rather than a romanticized scenic view. Take William Strutt’s (1825-1915) drawings in the Alexander Turnbull Library, which diary his two years in New Zealand from 1855 and 1856, in an attempt to embrace the pioneering life.

Strutt, an academy-trained artist, abandoned the relative comforts of England and Europe, turning his back on the “glories of art, the study of Raphael, Michael Angelo and the great Masters,” to purchase a hundred-acre block of land about ten miles from New Plymouth.2 While Mt Taranaki enthralled Strutt, who described “its summit crowned with perpetual snow, glittering in the clear air of the region” and later made several paintings in which it featured prominently, he had less empathy for the bush. He was intrigued by the “dark recesses” of the forest, but in his pictures, it serves either as a murky hiding place for Māori during ambushes of unsuspecting soldiers,3 or something to be brought under control to provide both space and materials for making a home.

Strutt’s self-portrait, which is often titled William Strutt as a New Zealand Bushman is highly suggestive of the play-acting that was necessarily part of his New Zealand experience. Here he dresses as the experienced pioneer: resting a hand nonchalantly on an axe, while his foot is placed in a conquering manner upon a fallen trunk. One hopes the tree behind is not going to invoke cries of ‘timber’ before he has had a chance to retreat to a position of safety.

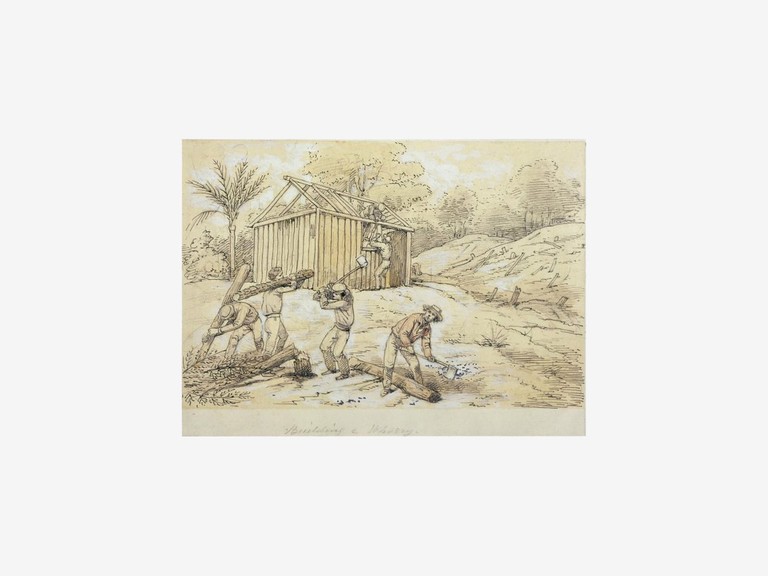

William Strutt, Building a whorry, 1855-6, pen drawing, 100 x 150 mm, Alexander Turnbull Library: E-453-f-012

After burning the bush to establish his clearing, a process Strutt likened to the “very picture of hell”, he and his Australian friends proceeded to erect a small “whorry” in which his second child was born. Although his garden flourished, the romance of the bush soon lost its appeal, particularly in terms of the feeling of isolation it engendered. He wrote of the “indescribable feeling of loneliness…the awful stillness of this spot, walled in by the mighty forest and shut out from all human intercourse…”4

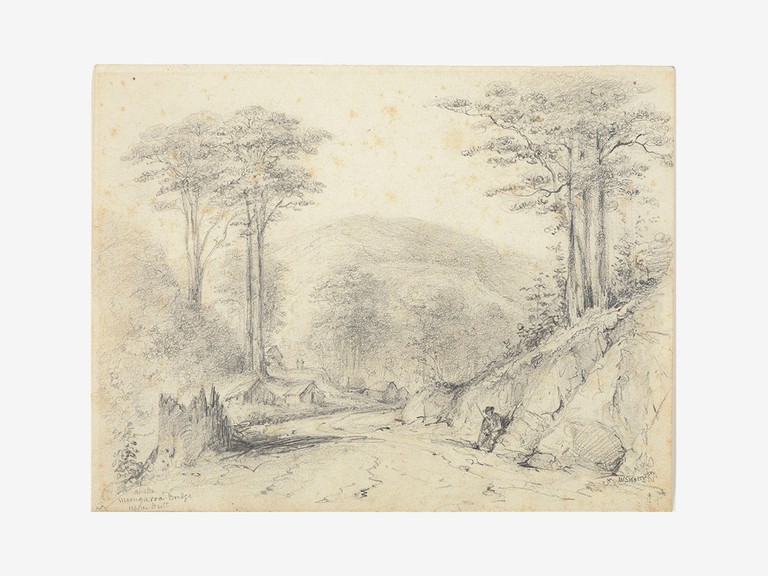

Strutt subsequently returned to Australia and within five years was back in England. Others were more permanently committed to their colonial experience, such as Edith Stanway Halcombe, daughter of naturalist and artist William Swainson, who grew up in the Hutt Valley. Swainson’s drawings regularly include tree-stumps as a formal and compositional device in the foreground, particularly in association with a view of the bush somewhat tamed, to accommodate a road, or a small building.

William Swainson, At the Mungaroa Bridge, 1848, pencil, Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa: 1992-0035-1922

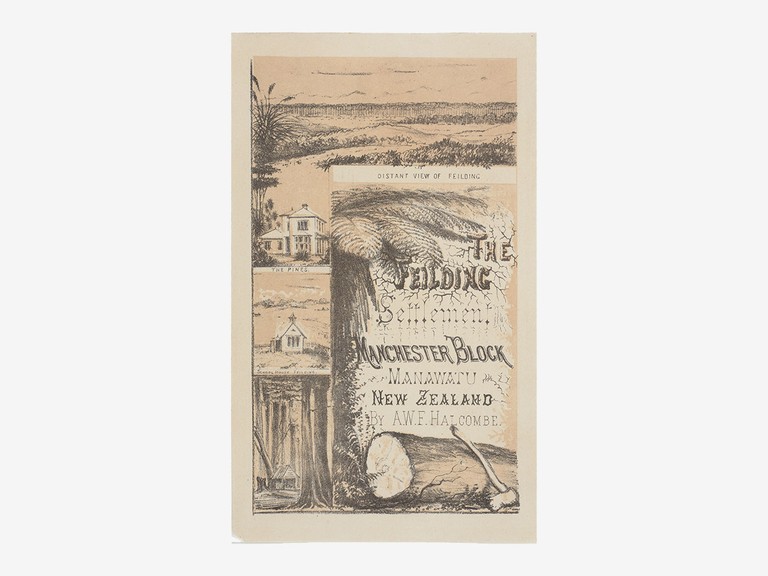

Edith learnt drawing from her father, and indeed, often copied his drawings. She later married Arthur Halcombe, the Agent responsible for settling the Manchester Block in Feilding. In an account of progress in 1874, Halcombe commented on the forest:

The block is covered with bush. Much of this bush is kowhai forest, very light, and easily cleared; but there are also large blocks covered with very valuable timber – matai and rimu – interspersed with totara trees; and large groves of magnificent totara occur in every direction over the block.5

For Halcombe, the ‘bush’ was seen purely in terms of a timber supply with a finite life. He concluded his report thus:

What with the railway formation at present, the timber supply when the railway work is finished, the formation of internal roads and tramways, the cultivation of the land when the timber is gone… I see no reason to fear that for many years to come there will not be ample and renumerative employment for a very large number of workmen… and when the Manchester Block shall have been stripped of its timber, a similar process of colonization carried on over the adjoining lands.

No wonder then, that Edith Halcombe’s lithographs, made to supplement a small booklet celebrating the Manchester Block, grounded the ambitions of the settlement in the taming of nature. The booklet was primarily to act as propaganda to encourage immigration, hence the motif of the fallen log and the axe feature prominently, almost as a full stop or exclamation mark to the title. Note that the exotic tree-fern is allowed as a decorative framing device, but the primary message constitutes the bringing of civilization to a new land, with the establishment of homesteads, churches and a cultivated view.

Edith Stanway Halcombe, Title page: The Feilding Settlement, Manchester Block, Manawatu. N.Z., c. 1878, lithograph, Te Papa: 1992-0035-1874/1-12

More curious in terms of its apparently deliberate placement, is the axe in the foreground of several of W. T. L. Travers photographs. Travers was one of those who was outspoken regarding deforestation in the 1860s. He, along with Potts, took on board the arguments of the American George P. Marsh, author of Man and Nature (1864), a timely evaluation of man’s impact on the environment. Crucial to Marsh’s argument was that the destruction of forests wrought havoc on ecological systems. Travers and Potts both referred to the change that had taken place in the character of the Hutt River since settlement, as the destruction of forests in the ranges precipitated the rainfall into the river with great speed, resulting in the now common flooding that occurred.6

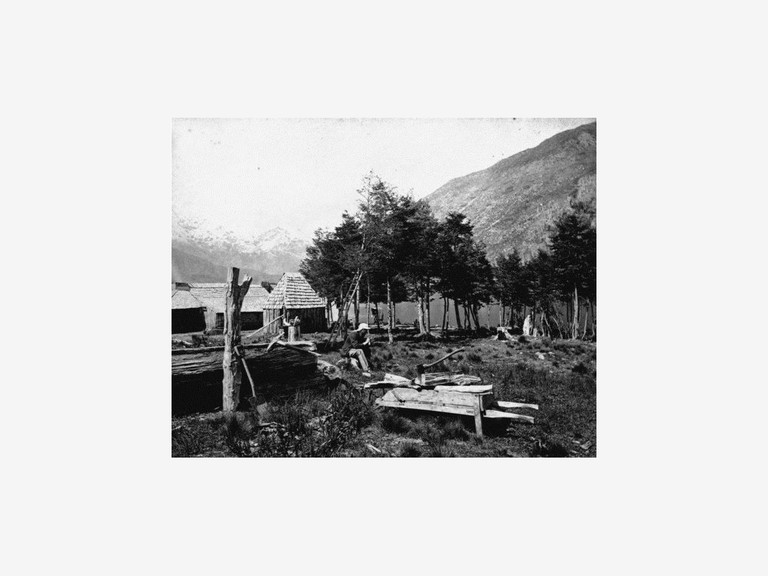

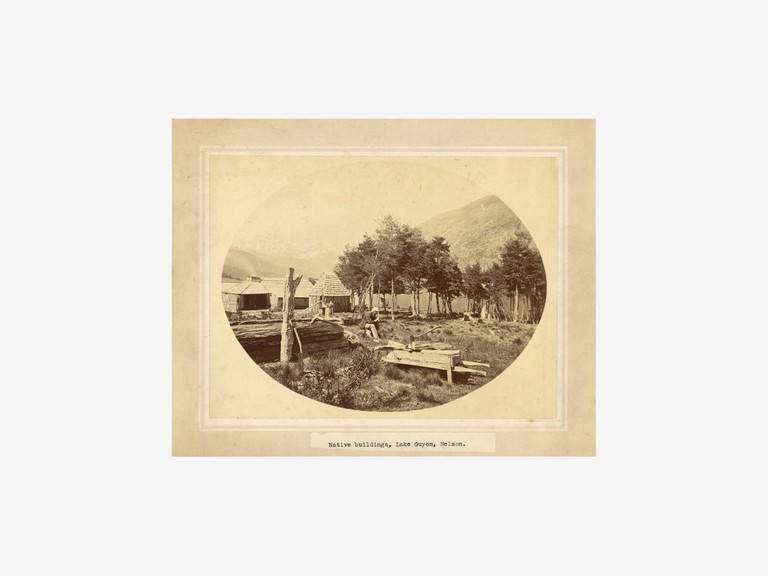

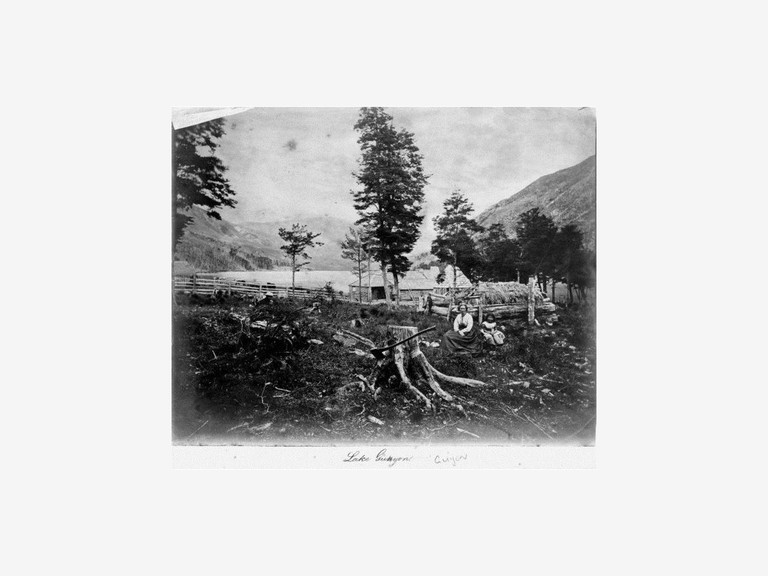

Consequently, the persistence of Travers’ axe in the photographs here strikes an odd chord. In the first three photographs (the second being a cropped and mounted version of the first, presumably for exhibition),7 the same wheelbarrow full of wood with an axe firmly lodged in the uppermost log features as a kind of prop in each foreground. In the last, the axe is struck with an almost theatrical blow into the tree-stump, demanding our attention.

William Thomas Locke Travers, On the shores of Lake Guyon, c.1870s, black and white negative, Alexander Turnbull Library: 1/2-019860-F

William Thomas Locke Travers, Native Buildings, Lake Guyon, Nelson, c.1865, albumen print, ATL: PAColl-1574-01

William Thomas Locke Travers, Lake Guyon, black and white photograph, c.1860s, ATL: PAColl-1574-30

William Thomas Locke Travers, Mr William Newcombe and family on the shores of Lake Guyon, c.1870s, black and white negative, Alexander Turnbull Library: PA7-22-04

How much was Travers, as Tim Bonyhady suggests in his account of “artists with axes” in Australia, complicit with the making of views through the cutting down of trees?8 Was this motif included as a reminder of the destruction being wrought on the New Zealand environment, or simply serving a documentary purpose as illustration of what was required to construct a dwelling in the new colony?

Much as I wish to read a conservationist message into these photographs, Travers’ position is as complex as all colonial figures. In his newspaper articles and in the text he wrote for the New Zealand Graphic and Illustrated, 1877, Travers considered the contradictory impact of systematic colonization, stating:

It is to be much lamented that the progress of improvement, in the general features of the country is leading to the complete destruction of this elegant vegetation in the neighbourhood of the principal towns, the immediate effect being to impart an aspect of ruggedness and desolation from which it is difficult to suppose they can ever recover.9

In spite of these lamentations, Travers simultaneously praised the progress of colonization. In a paper presented to the New Zealand Institute, in 1869 Travers celebrated the fact that:

We have, indeed, on all sides of us abundant evidence that the energies of a European race are rapidly converting a country which in its natural state scarcely afforded means for the sustenance of man, into one capable not only of maintaining a contented population, but of affording the materials for an extended foreign commerce.10

Given these photographic views are all taken on Travers’ station on the shores of Lake Guyon, we probably can read them as a celebration of colonization. Perhaps the lament comes later, or only when detached from personal affairs.

Artists as activists

One thing is sure; photographers did not share the luxury of painters when it came to making a picture. As the watercolourist Alfred Sharpe advised in his “Hints for landscape students in watercolour’:

You should give some thought to the grouping of the objects in your foreground, for in this part of the picture it is allowable to alter the position of the various objects, if desirable, and to regroup them in a more picturesque manner; but I would only do so when the grouping, as it is, is decidedly ugly or unartistic, a thing that seldom occurs in New Zealand. For instance, a large tree might divide the picture into two in the worst position possible, ie. the centre; when this occurs you can remove it more to the right, or left, or leave it out altogether.11

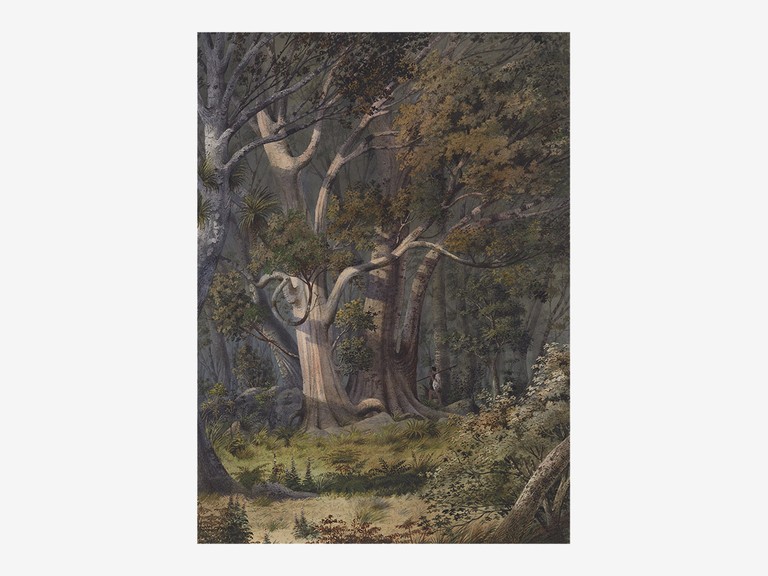

Alfred Sharpe is notable in nineteenth century art history for his voicing of concerns around the destruction of the New Zealand forest. Conservation centers on the belief that “natural features should be preserved for their inherent value… so they can be appreciated rather than exploited by future generations”.12 Conservation was key to Sharpe’s writing, which was regularly published in the press under various pseudonyms. In 1881 he asked the citizens of Newmarket, “Do they know that these trees are disappearing yearly wholesale, for triumphal arches or Christmas decorations or larrikin destructiveness…”13

Earlier he had pictured a jam of kauri logs in a creek near Papakura. The logs lay like some fallen classical columns. Perhaps Sharpe pictured them in a foreboding sense, imagining the colonial enterprise perversely as a civilization in decline. This sentiment continued, in 1886, nearly 20 years after Potts and Travers, he wrote:

There are still some fine kauri trees near the Waitakerie [sic] Falls; which, though nearly inaccessible just now, may be easily reached in another decade. Would it not be wise to reserve at least one of the best clumps there, so that the next generation may see what kauris were like?…Could not Government be induced to reserve a few hundred acres of the best of it that future generations may arise and call us blessed?14

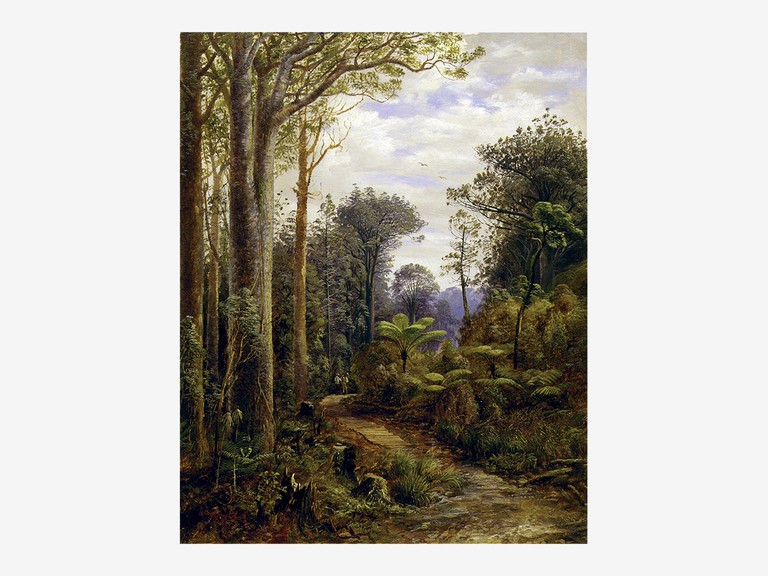

The Waitakeres were also a favourite haunt of Charles Blomfield, an artist best known for his views of the Pink and White Terraces at Rotomahana. Unlike Strutt, who felt isolated in the bush, Blomfield reveled in it. “I never tire” he wrote “of its wonderful charm. I love the glinting sunlight and the mysterious gloom, the sweet smell of moist air and the resinous perfume of the pines.”15 Blomfield’s bush scenes are intimate studies of a landscape he perceived as thoroughly charming. Among the Kauris, Waitakeres, 1884, was proudly painted on site, and captures the sylvan nature with which Blomfield envisaged the New Zealand bush.

Charles Blomfield, Among the Kauris, Waitakeres, 1884, oil on canvas, Te Papa: 1944-0002-1

He too, though, expressed angst over the settler attitude to the bush:

It seems nothing short of a crime to destroy so much beauty, but the bushman’s axe and settler’s fire are playing havoc with the finest parts of it. The settler regards the bush as so much waste land. He is ever thinking of how much grass or turnips he could grow there.16

Perhaps, though, we will let Sharpe have the last words and join him in his salute, hoping that 140 years on, we might continue to be more enlightened as a culture in our responsibilities to the mighty trees that remain.

The firestick of the settler is devastating square miles of magnificent forest at a time; his axe is laying the monarchs of the forest low, one by one, and his cattle are breaking down and destroying all the lovely undergrowth, and spreading the seeds of European grasses and plants everywhere, which seeds grow so vigorously that they soon strangle the delicate native vegetation of the country. I never go into the forest without seeming to hear from every bosky covert of virgin greenery the sad, sad words, ‘Morituri te salutant’ – ‘Those about to die salute thee’.17

Alfred Sharpe, Burial place of Hone Heke, Bay of Islands, 1883, watercolour. Purchased 1977 with Ellen Eames Collection funds. Te Papa 1977-0027-1

About the author

Dr Rebecca Rice is Curator Historical New Zealand Art at the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. She researches and publishes in the field of colonial New Zealand Art with a particular focus on the histories of exhibition and display. She has contributed entries on colonial New Zealand artists to Art at Te Papa (2009); a chapter exploring the colonial context ofNineteenth-century Auckland for Art Toi: New Zealand Art at Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki (2011); and has written an essay Lindauer’s Maori at Home and Abroad for the catalogue accompanying the exhibition Gottfried Lindauer’s Maori Portraits, Berlin (2014). She curated Van der Velden: An Art of Two Halves at Te Papa (2013) and convened a symposium considering his impact on New Zealand art. She is currently researching towards an exhibition of the visual legacy of the nineteenth-century New Zealand Wars at Te Papa for 2016.

-

1.

Julius Vogel, New Zealand Parliamentary Debates (NZPD), XVI (1874): 93. Cited in Graeme Wynn, “Conservation and society in late nineteenth century New Zealand,” New Zealand Journal of History 11(1) (1977): 124.

-

2.

William Strutt, Autobiography of William Strutt, 1850-1862, National Library of Australia: NK 4367, p. 89. Cited in Heather Curnow, The life and art of William Strutt 1825-1915 (Martinborough: A. Taylor, 1980).

-

3.

See William Strutt, The Ambuscade (1867), oil on canvas, Fletcher Trust Collection, http://fletchercollection.org.nz/item.php?id=701

-

4.

William Strutt, Autobiography of William Strutt, 1850-1862, National Library of Australia: NK 4367, p. 99. Cited in Heather Curnow, The life and art of William Strutt 1825-1915 (Martinborough: A. Taylor, 1980).

-

5.

“The Feilding Settlement: Mr Halcombe’s report,” The Wellington Independent, May 19, 1874, np.

-

6.

The Lyttleton Times, October 23, 1868, p. 2.

-

7.

Travers exhibited his photographs at many international exhibitions in the nineteenth century, including Vienna, 1873, Philadelphia, 1876, Sydney 1879 and Melbourne 1880.

-

8.

Tim Bonyhady, ‘Artists with axes’, Environment and History, 1 (1995): 221-239.

-

9.

New Zealand Graphic and Illustrated, (London: Sampson, Searle and Rivington, 1877), 2. This publication was illustrated by Charles Barraud and scripted and edited by W. T. L. Travers. It aimed to show scenery from various parts of the colony without focussing on the towns.

-

10.

W. T. L. Travers, “On the changes effected in the natural features of a new country by the introduction of civilized races,” Transactions and Proceedings of the New Zealand Institute, 2 (1869): 312.

-

11.

Roger Blackley, The art of Alfred Sharpe (Auckland: Auckland City Art Gallery, 1992), 137.

-

12.

Simon Nathan, “Conservation – a history - Soil conservation,” Te Ara - the Encyclopedia of New Zealand, http://www.TeAra.govt.nz/en/conservation-a-history/page-5 (accessed October 30, 2014).

-

13.

“Asmodeus is again ethnologically inclined,” New Zealand Herald, May 14, 1881, p. 6. Cited in Blackley, op cit. p. 124.

-

14.

“Asmodeus Moralisations,” Observer and Freelance (January 2, 1886): 11. Cited in Blackley, op cit., p. 128.

-

15.

Charles Blomfield, cited in Muriel Williams, Charles Blomfield: his life and times (Auckland: Hodder and Stoughton, 1979), 65.

-

16.

Blomfield, cited in Williams, 168-9

-

17.

“Picturesque New Zealand. Notes by an artist and tourist “off the beaten track”, Illustrated Sydney News (January 3, 1891): 18.