The Occasional Journal

The Dendromaniac

March 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton, Jessica Hubbard -

For the trees

Rachel Buchanan -

dwelling trees, tree dwellings

Xin Cheng -

Axis Mundi: Long Live the Tree of Life

Prudence Gibson, Tessa Laird -

Forest satyagraha

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Garden City

Holly Best -

Accentuated Breath

Clare Hartley McLean -

On the portraiture of mushrooms

Creek Waddington -

Shade

Andrea Gardner -

bigwoods

Emil McAvoy -

Regan Gentry: Transformer and Master of Time

Sharon Taylor-Offord -

Colonisation versus conservation: a colonial view

Rebecca Rice -

Tae

Bridget Reweti -

The Framing of the Earth

Richard Shepherd -

Wildness in the Garden of Empire

Shaun Matthews -

In search of unknown vandals

Bronwyn Holloway-Smith, Thomasin Sleigh -

Bo.tan.i.cal: from the Greek

Jessica Hubbard -

The Tree as Traveller: Sakura in space, kōwhai in Chelsea, and the oldest pohutukawa in Spain

Emma Ng -

Seeing the wood and the trees: a complicating history of Hitler’s Oaks

Ann Shelton -

Conversations with Cripplewood

Cat Auburn -

Out of the Woods: The Return of Twin Peaks

Alice Tappenden, Matt Plummer -

The conceptual, the pastoral, and the plainly freakish (or, some of my favourite artworks are trees…)

Martin Patrick -

This is a femme slam.

Sian Torrington -

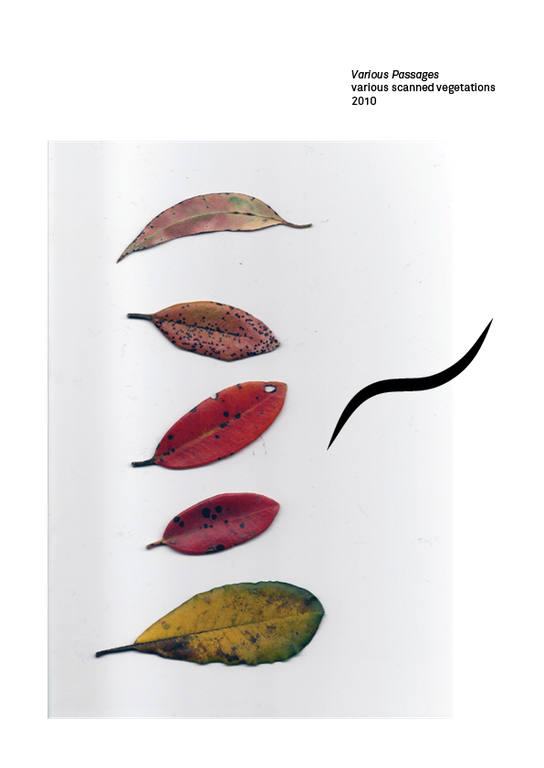

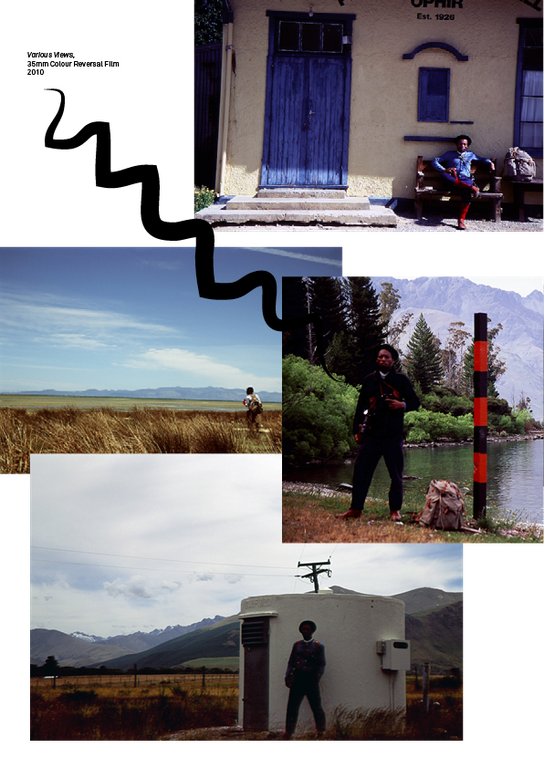

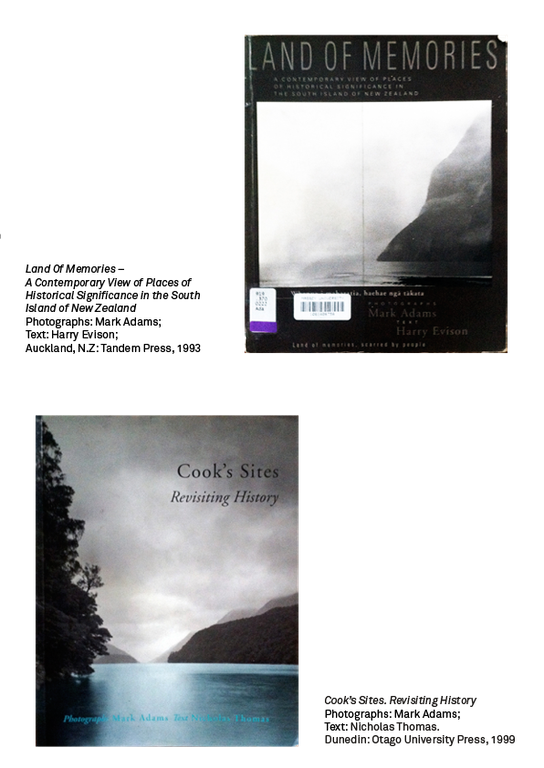

Explorations

Christian Nyampeta -

Works from the series An Ethnography on Gardening, 2006-2008

Raul Ortega Ayala -

Bent

Jonathan Kennett, Mary Macpherson -

One Shining Gum / Savia Brillante

Christina Barton, Maddie Leach, Zara Stanhope -

Acknowledgments

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton

Explorations

Christian Nyampeta

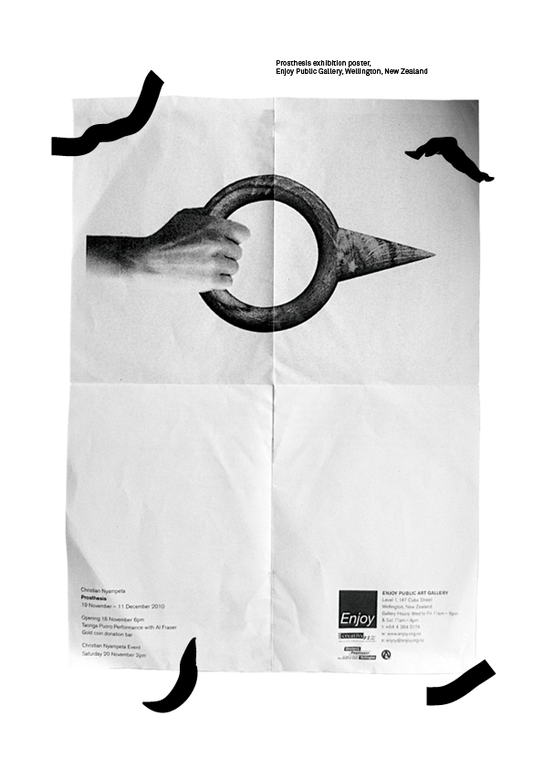

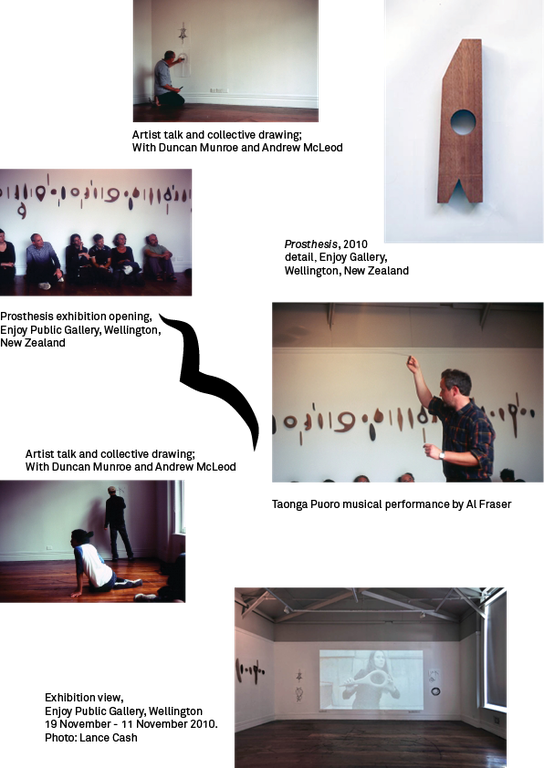

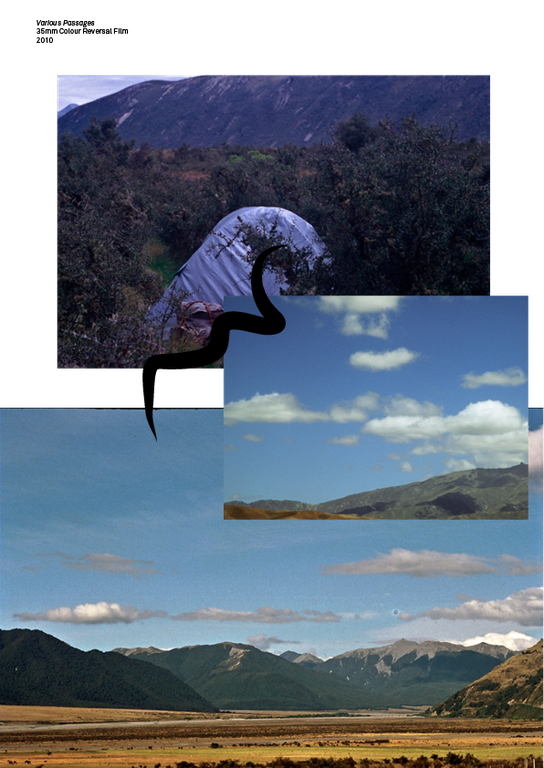

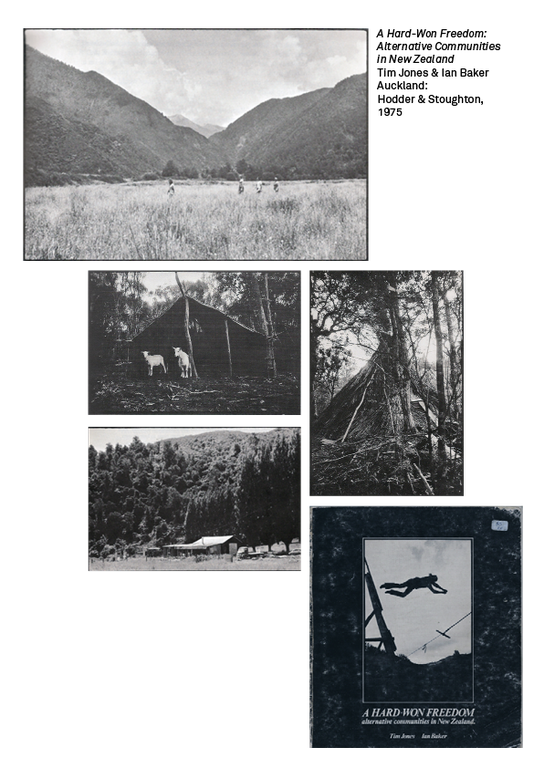

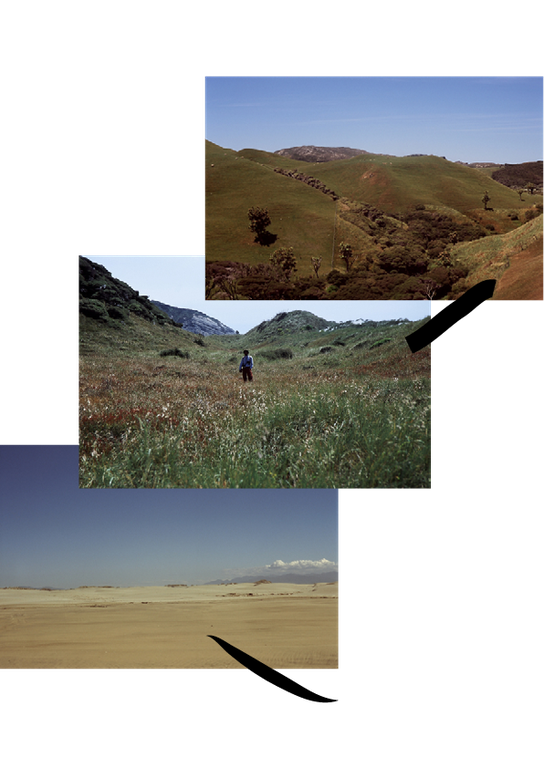

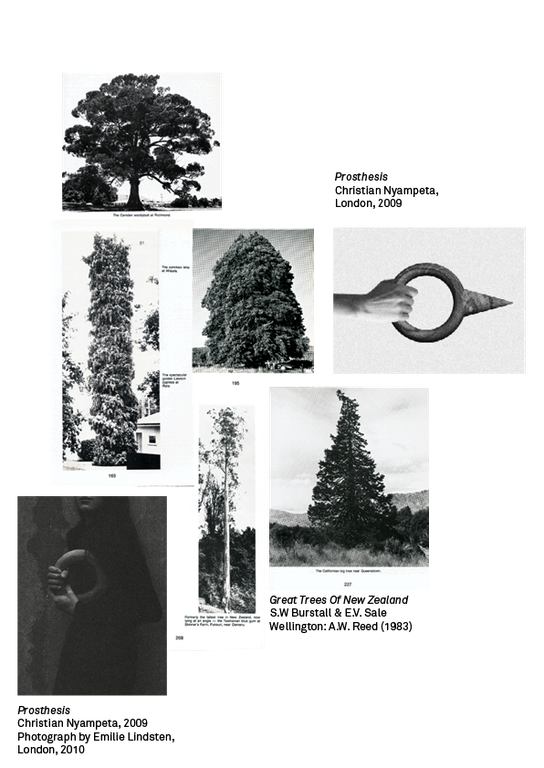

As the last two months of 2009 were fading into the past, I visited New Zealand on the occasion of my exhibition, Prosthesis, at Enjoy Gallery in Wellington.1 It had been over a decade since the only time I had boarded a long haul flight, with that first voyage being an exodus from Nairobi to Amsterdam. As such, journeying from London to Wellington by way of Tokyo and Auckland felt like an odyssey of sorts, transversing time and space, shuttling across one fragmentary but consistent order, to another reality altogether of a somewhat unnamable truth. My second journey provided a fictional setting in which I conversed unexpectedly with a memorialised past. Such memories revealed themselves in the reflection of these new surroundings, which evoked analogies between the pleasures of the great outdoors and the predicament of exile.

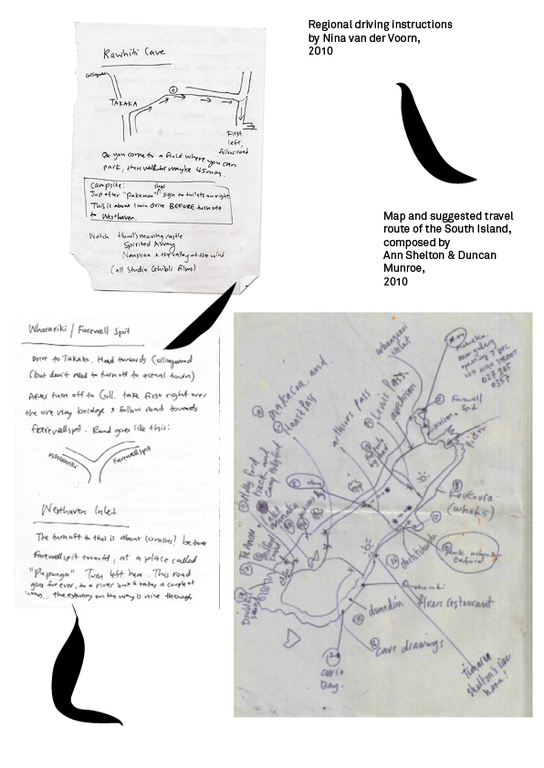

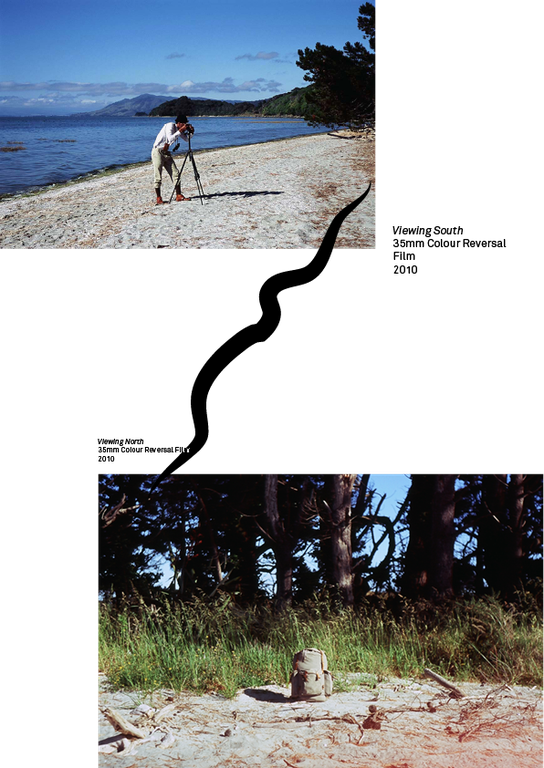

Once the gallery activities at Enjoy were completed, I embarked on a solitary journey across the South Island. I took off equipped with a map drawn and annotated by the hands of my generous hosts, a set of rudimentary camping equipment and a number of books. A book mentioned that when passengers arrive, they look dazed from the trip, as if they had just wakened from a long sleep. They stare at us, their voices unsteady, either too soft or too strong, because they are not sure they are understood, even by their acquaintances. They are insecure, they don’t know if the language they speak is the right one. They wonder if they have arrived at the right station, though it is difficult, after all these verifications, to get anywhere else but where one is destinated! We feel out of place, since we travel with our illusions. Even though they may feign otherwise, travellers hesitate to get off the vessels, to leave their element and everything else. The friends who meet them have the same dazed expressions mixed with worried looks that explain the awkward and embarrassed greetings. Here is a passenger who looks with bewilderment in all directions, rolling his eyes, while his ears remain blocked. He answers automatically, obviously missing the point. The new arrivals bring preconceived ideas, their eyes check the surroundings before accepting them. As soon as we arrive, we have to start again for another destination, check our luggage, be careful, even suspicious, since the last thing we need now is to lose something. The family members sent to welcome the traveller are eventually introduced, but the latter confuses the names and the degrees of the relationship. So to help him out of his embarrassment, they ask: Are you sure you haven’t left anything behind? They find excuses of one sort or another. Did you leave on time? Who took you to the station?2

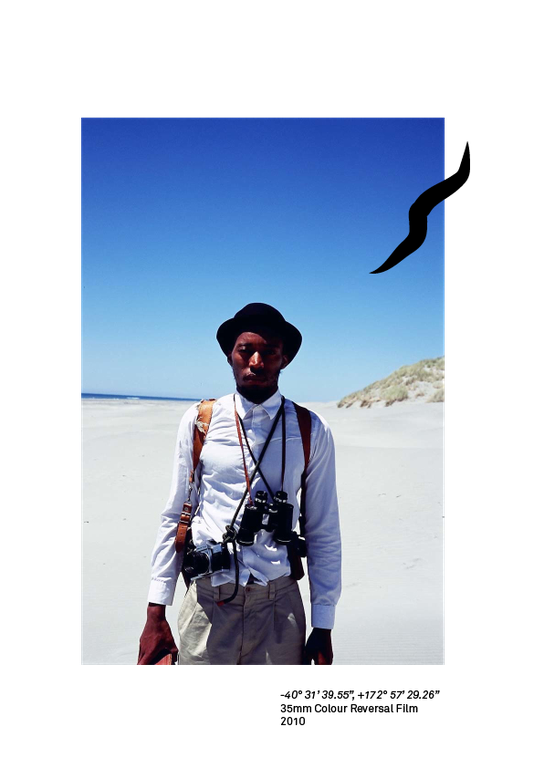

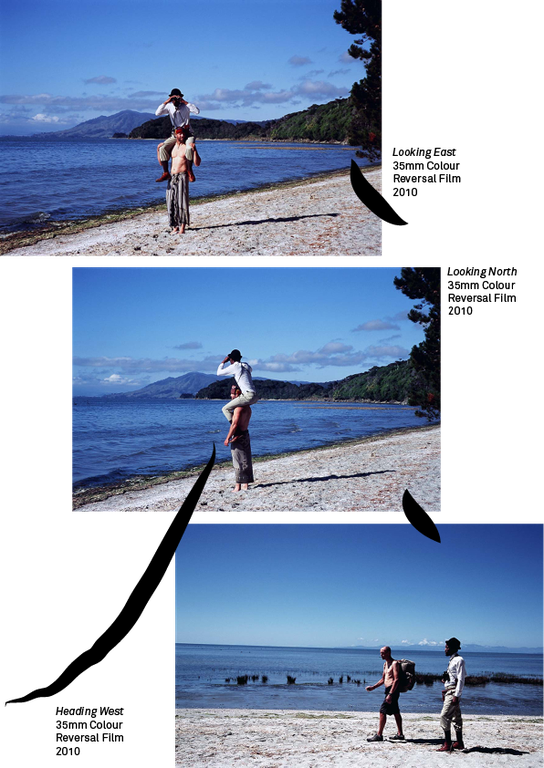

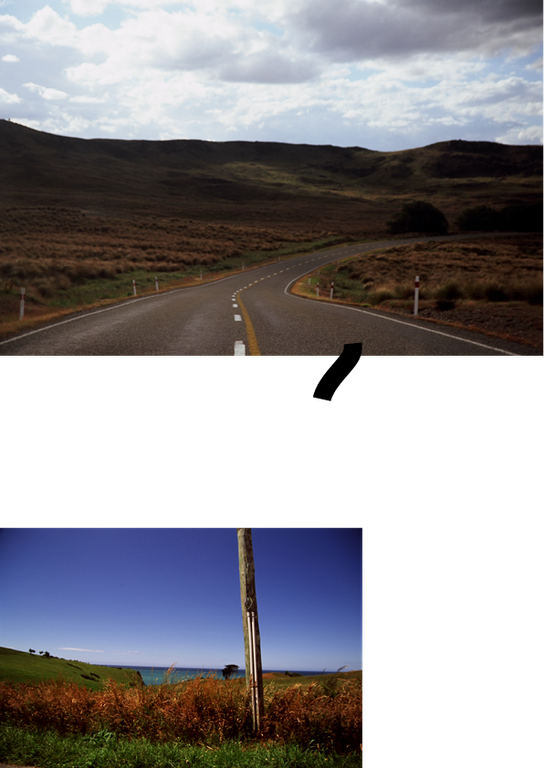

The early morning ferry had turned, and by now it was offering its shadow to face the burning sun. At about the moment when the jovial rays were urging my senses to seek a more sheltered seating, our arrival was announced and we reached the port timely and effortlessly. About noon I collected a rental car, upon which I made my way following my hosts’ recommendations. The scenes succeeded memorably, each new vista heightening the parallels of the road, the bird songs, the smell, the colours, the foliages, the temperatures, the interpellations. It was time to look, to take in, to observe, to notice, to ignore, to acknowledge, to slow down, to recognise, to accelerate, to halt, to pause. At times I would look exhilarated, at others I must have appeared dumbfounded, staring at occasional faces here and there.3

Then the night fell upon earth on a bright sanded beach, caught between the restless foams of the shore and the cutty grass that ceded to a forest of pepper trees growing over tussocks of bracken fern. The stars came into the sky in laughing groups, while the numerous comets scratched their way onto the limpid vault of the firmament. The mendicant stars were animated, as if they were pieces of chalk in the grip of a mighty savant, making a mystery of everyday sights. Night has the appearance of divinity. It smells like infinity. Day will never be more than a pathetic crater of a sickly light. Only the night has things to say to the soul. Only it can unite our bodies with the vast truculence of the universe.4 That is how my invocation went as I fell asleep.

When the light cast off its night-dress and slipped into a vivid drapery, I swam. I dived and enjoyed the water, while on the bank my clothes and my bag roasted in the growing rage of the sun. I laid my heart on the water’s coloured limpidity, on its shaky smell and its salty taste, and revelled in the delicious contact with the sand and the coolness of its flesh, in the scuttles of the aquatic biologies and, on the opposite bank, the dense flight of the shorebirds. I enjoyed, too, the sensual lapping and gurgling of the water choked with peace, sighing and speaking with its liquid voice. At one moment I stepped out of the water and walked on the stones for the sheer pleasure of walking. I chased the birds as I’d done when I was a child. The stones were warm. Crowds of unknown ants had settled on them to sleep their reflective sleep. I rolled on the sand, then on the stones. Behind me, the waves threaded a hundred schemes that burst like soap bubbles.5 An eternity flashed by and when I stood up, I put on the same clothes which I fitted rather differently. Then a murmur was heard.

I spent a decade there without even knowing it. Every empty mile, every breath of graveyard wind had my name on it. A name like mine, arrogance like mine. I just never realised it until I stood on it, set my foot with my flesh instead of my mind, my imagination.6 I wasn’t sure if I would succeed. There was nothing to win. In the engulfing distance in which I had enlisted myself, I made sure to increase the unpredictable, this endless supplier of abysses. I was an aggression without assault, an invisible takeover. Moved by obscurity, I went from crossroads to crossroads, the resonance of the past still reverberating at every turn. I was visited. And they came together, to this current world, on the shores that arose in me, and predicted what is most essential—a murmur.

The world discretely emerged through, stripped from the confines of speech. With little measure, I was thrown into a dispersion of seas, earths, waters, ices, fires, deserts, jungles, shelters, flesh, rocks… But I wasn’t alone! I wasn’t alone. The masters of the imaginary were on my side. I was no longer a messenger, nor a traveller: I became a warrior, with all the weight of this word, bringing peace amongst irreconcilable forces, performing unyielding gestures, provoking doubtful bursts of laughter and ironic rituals, devising rigid and fluid frameworks, sparking lucid lights and beliefs, resisting brute desires for embalmed mummies. I was a warrior of the imaginary. A life virus, a retro-rebel, a marginal poet, the burden of derail, of expel. An opponent. An aggressor without aim, a dreamer without ideal. The imaginary was indestructible. It knew no bounds. No turrets, no armies, or bullets. It appeared nowhere and intimated itself everywhere.7

For days on end I drove, as if looking for something without knowing what it was. Sometimes we react to the truth as if we were capable of altering it. We stick the whole blade of our powerlessness into it. But it shows its teeth and its transparence. We act as if we were able to negotiate our journey. In fact, neither time nor truth belong to us. Truth hates us. We have nothing in common with it, it is indifferent to us. Yet, right in front of us, is the deep beauty of things. Even if that sea out there has eaten our dreams, it is no less beautiful in its robe of mystery and studded with an abundance of lives. The way the sea has of taking the sky in its arms!8 That was how my thinking went as the wheels covered the road. The elusive motion of velocity fascinated my mind; I was captured by the spell in which movement changes, for instance, a mere shed into a consummate sculpture. As I drove by, the edifice’s angles were thrown into a mild panic, like the sea when it is awaiting a storm.

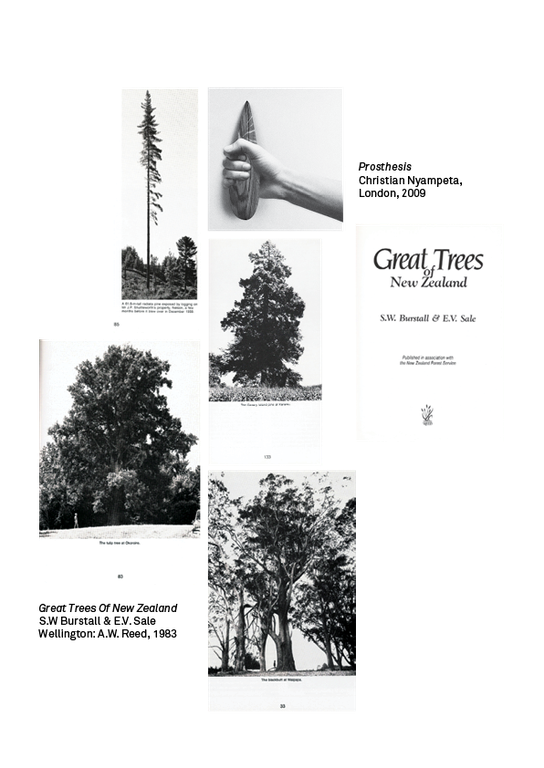

The landscapes rolled past, the sceneries scrolled by, changing from the verdure of the meadows to the thickets of the flax, from the brooks to the copses. While my mind reversed in the direction of the equator, the peaceable mantle of Pacific flora wandered by. Waving like signposts, there were the tall saplings of white pine, the crimson christmas tree near the shores, the cabbage tree, the towering kahikatea, the red pine, the nikau, the puriri and probably many others.9 Springs followed waterfalls. And when I reached an interior mountain, I felt a calling and I climbed for some hours. While a tormented rain fell on the deserted paths, the formidable profusion of the beech-podocarp dowsed in the torrent, the fronds of the silver tree ferns drenched in the damp, the supplejack continued its skywards journey. The birds were quietly listening to the downpour of the skies. The unabated torrent slipped the land, and creeks burst out their banks and gushed through the path, sweeping with them the hesitantly rooted trees downwards.

At the moment when I reached the heights, the ponderous clouds had enveloped the summit into an opaque mist of humid powder. I love the murmur of the clouds, I liken these to infinite sheep: they feed on the green plain of my heart.10 I took seat on one of the innumerable large rocks glistering off the rain. I rested and caught some breath. All of a sudden the mist lifted as if it was a curtain torn apart by a celestial blow. In that instant, the mountain revealed far more majestic peaks that soared silently over a crystalline lake contained inside a monumental crater. The effect of this unexpected vision was of such an intensity that I was seized by a tremendous shudder. I screamed and began an incoherent dance on top of the sharp and slippery rocks. My body felt light as air, as if I had been freed from the pull of gravity. At the same time, I was filled with a feeling of absolute pleasure and peace. My heart melted inside my breast. I had never before felt myself so true, so happy, so at one with everything. My senses were transported beyond anything they had experience before. The light became like nothing I can describe.11 I experienced a piercing clarity, the likes of which I had never encountered before. This must have been the mountain’s invitation for dreaming another dream.

About the Artist

Christian Nyampeta is a London based artist. Recent exhibitions include How to Live Together: Prototypes, The Showroom, London (2014) and How to Live Together, Casco and Stroom Den Haag, Netherlands (2013-14). He is an MPhil/PhD candidate at the Visual Cultures Department of Goldsmiths, University of London.

All efforts have been made to contact the copyright holders, if you are the copyright holder please contact Enjoy Public Art Gallery.

-

1.

Christian Nyampeta, “Prosthesis”, Enjoy Public Art Gallery.

-

2.

Extract adapted from Felix Tchicaya U Tam’si, The Madman and the Medusa (Charlottesville: The University Press of Virginia, 1989).

-

3.

Extracts adapted from: Sony Labou Tansi, The Seven Solitudes of Lorsa Lopez (London: Heinemann, 1995).

-

4.

Ibid.

-

5.

Ibid.

-

6.

James George, Ocean Roads (Wellington: Huia Press, 2006).

-

7.

Adapted extract from Patrick Chamoiseau, Écrire en pays dominé (Writing in a Dominated Land), Trans. Jean-Paul Martinon (Paris: Gallimard, 1997).

-

8.

Extracts adapted from: Sony Labou Tansi, The Seven Solitudes of Lorsa Lopez (1985)

-

9.

S.W Burstall & E.V. Sale, Great Trees Of New Zealand (Wellington: A.W. Reed, 1983)

-

10.

Christian Nyampeta, Anachoresis, essay film commissioned by Casco – Office for Art, Design and Theory, Utrecht, the Netherlands, in the context of How To Live Together (2013), extract adapted for screen from Nimrod Bena Djangrang– Le départ, Arles: Actes sud (2005); extract translated by Christian Nyampeta, http://cascoprojects.org/how-one-can-leave-our-beloved-ones-with-such-joy

-

11.

Extracts adapted from: Sony Labou Tansi, The Seven Solitudes of Lorsa Lopez.