The Occasional Journal

The Dendromaniac

March 2015

-

Editorial

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton, Jessica Hubbard -

For the trees

Rachel Buchanan -

dwelling trees, tree dwellings

Xin Cheng -

Axis Mundi: Long Live the Tree of Life

Prudence Gibson, Tessa Laird -

Forest satyagraha

Robyn Maree Pickens -

Garden City

Holly Best -

Accentuated Breath

Clare Hartley McLean -

On the portraiture of mushrooms

Creek Waddington -

Shade

Andrea Gardner -

bigwoods

Emil McAvoy -

Regan Gentry: Transformer and Master of Time

Sharon Taylor-Offord -

Colonisation versus conservation: a colonial view

Rebecca Rice -

Tae

Bridget Reweti -

The Framing of the Earth

Richard Shepherd -

Wildness in the Garden of Empire

Shaun Matthews -

In search of unknown vandals

Bronwyn Holloway-Smith, Thomasin Sleigh -

Bo.tan.i.cal: from the Greek

Jessica Hubbard -

The Tree as Traveller: Sakura in space, kōwhai in Chelsea, and the oldest pohutukawa in Spain

Emma Ng -

Seeing the wood and the trees: a complicating history of Hitler’s Oaks

Ann Shelton -

Conversations with Cripplewood

Cat Auburn -

Out of the Woods: The Return of Twin Peaks

Alice Tappenden, Matt Plummer -

The conceptual, the pastoral, and the plainly freakish (or, some of my favourite artworks are trees…)

Martin Patrick -

This is a femme slam.

Sian Torrington -

Explorations

Christian Nyampeta -

Works from the series An Ethnography on Gardening, 2006-2008

Raul Ortega Ayala -

Bent

Jonathan Kennett, Mary Macpherson -

One Shining Gum / Savia Brillante

Christina Barton, Maddie Leach, Zara Stanhope -

Acknowledgments

Alice Tappenden, Ann Shelton

The Framing of the Earth

Richard Shepherd

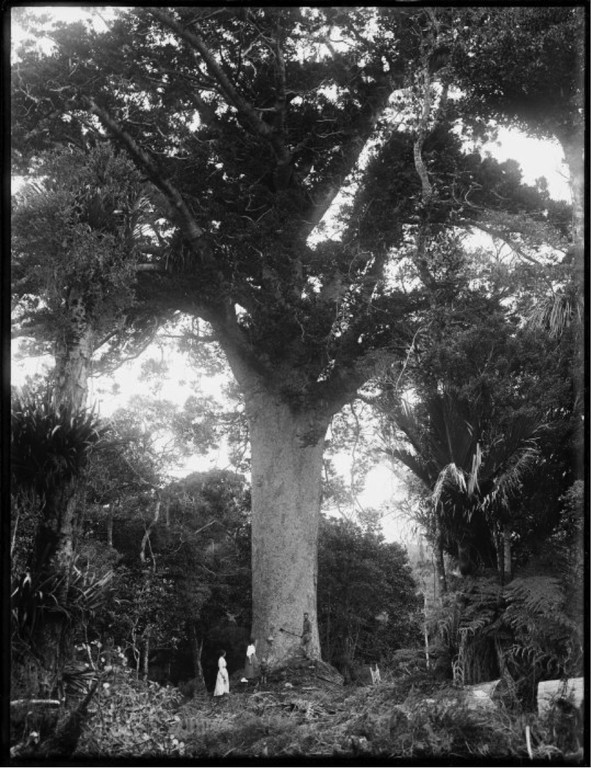

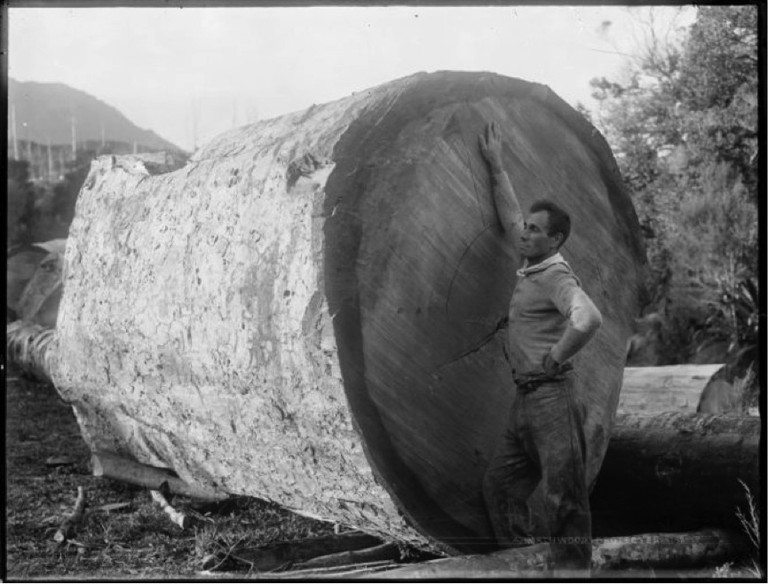

In April 2014, television news reported the story of a “black gold rush” taking place in Northland, New Zealand. Ancient, fossilised kauri logs, around 30,000 years old, were being dredged from shallow earth, partially milled, stacked and exported to Chinese buyers; 2800 cubic meters in over 14 months. Since the 2008 free-trade agreement China has rapidly become one of New Zealand’s primary export markets, eclipsing Australia in 2013. The trade is in agricultural commodities, meat, pine, dairy, and recently swamp kauri. These primary industries produce some of the most dangerous conditions for workers and receive some of the heaviest capital investment. Indeed the government’s ambition is now to double agricultural output by 2025. The environmental toll of such a project will be immense. The boom and inevitable bust trade in ancient swamp kauri seems small fry in the wider context of the ongoing ecological crisis but its absurd asymmetries brings aspects of it into focus. The way the magnitude of geological time is rendered into so much “furniture”; the cynical justification of creating unsustainable jobs vastly disproportionate to the capital created by such ventures; the indifference to existing environmental protection policies - all this would boggle the mind if it weren’t just business as usual.

The story of the swamp kauri is part of what scholar Sean Cubitt calls the “history of environmentalisation”. He writes, “Since the 16th century in Europe, and throughout the world during the colonial epoch, land was taken out of the commons, made private property, and its inhabitants alienated from it. This is how land became environment, the thing that surrounds - the not-us.”1 This material process is facilitated by creative works of the imagination that ideologically constitute the land as real estate and promote an expansionist logic. The most well known New Zealand example of this is probably Charles Heaphy, who as an agent of the New Zealand Company from 1839, produced pictorial survey documents that were also reproduced in England as part of the publicity campaign to attract new migrants. There is now a flourishing literature on environmental history that examines the way the desire for progress and the mediating influence of ideologies transforms the topography of place. For ‘Nature’ to be recognised as such it must be corralled to the whims and waxing of human endeavour and desire, even if this is a desire to preserve.

The kauri forests have been a central icon in imagining Aotearoa New Zealand and historian Paul Moon has described how deeply embedded in the mythologising of European settlers and pre-colonial Māori they were.2 For Māori the forest was a source of food and materials for tāonga (cultural treasures). Trees embodied atua (spiritual deities) and so rendered the forest a tapu (sacred) site that required a multiplicity of cultural protocols in any human exchange with it. Moon writes, “Trees were intimately bound up in the imagination of individuals, and were never conceived of as merely objects. Instead, they were weighted down with spiritual significance and the embodiment of much of society’s mythology”.3 These legends were often sentimentalised by late nineteenth-century settlers as part of the effort to create their own mythology of progress and civilization. Moon quotes one zealous MP, Thomas Kelly, who told parliament in 1894, “[t]he best way of dealing with forest covered lands was to use it for agricultural purposes. The forest trees if not cut down and utilised would simply rot, they arrived at the state of maturity, and then declined…the best way of using the land was to get it under grass as soon as possible, and to get population on it”.4 Yet, by the turn of the twentieth-century, the ancient kauri (upright rather than underground this time) provided settlers with a sense of deep time and their own history. As the machinery of nationmaking threatened the existence of the forests, and displaced Māori from their ancestral homes and custodial obligations, the trees of the forests embodied the spirit of the colonial pioneer — broad shouldered, stoic and silent.

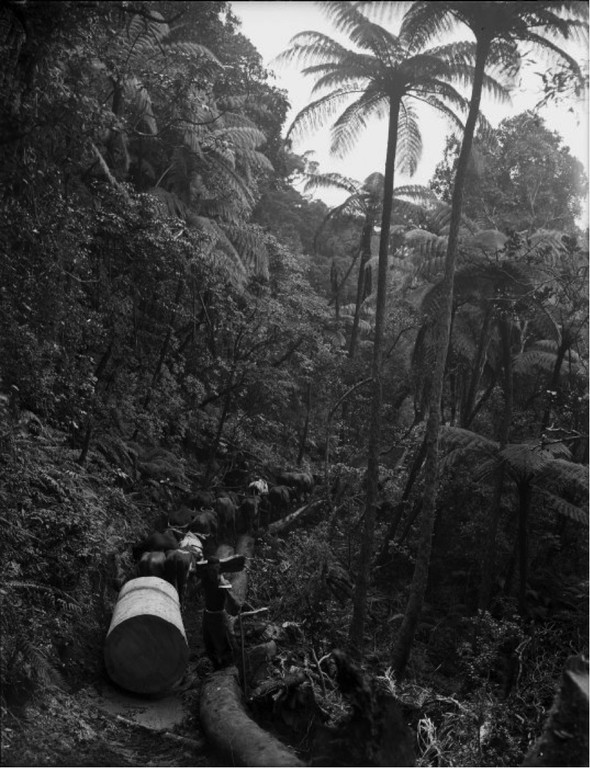

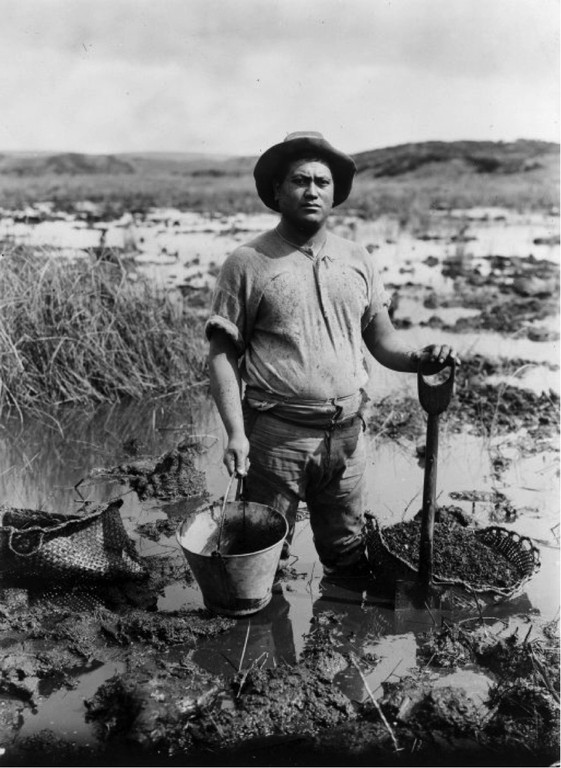

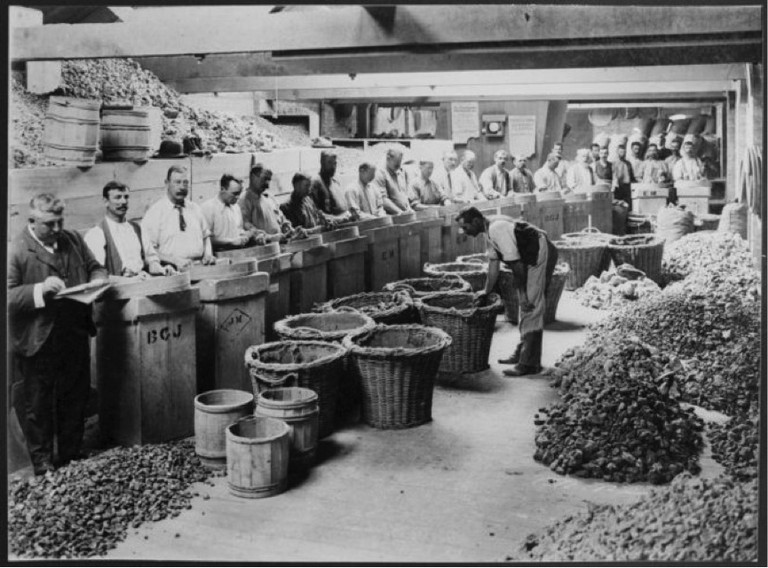

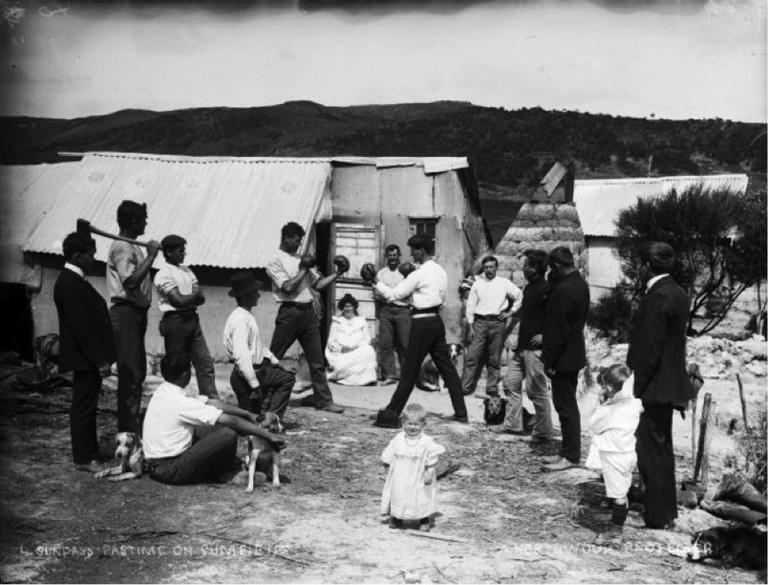

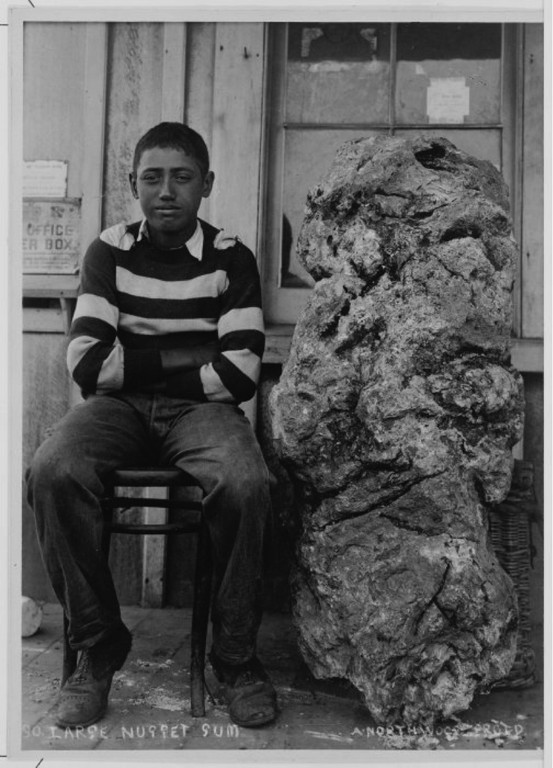

Below are reproductions of a selection of photographic and newspaper images deposited in the Alexander Turnbull archives. They are mostly from the period 1910 to mid-1920s and record the felling, transport and treatment of kauri products for trade. Almost all of these photographs were taken by the Northwood Brothers of Northland, Arthur Northwood being the primary photographer in the North. As well as timber, the selling of gum expressed through cracks in the bark and partially fossilised in swampy peatland was also a large industry — at one point the fifth biggest in the country. It had a myriad of uses from tattoo ink, fuel for lamps, linoleum and, apparently, a pleasant tasting chewing gum. Gum digging was popular with migrants from Central Europe and those without timber licences, including Māori. British subjects, however, resented these itinerant workers who mostly sent their earnings back to family in Europe. In 1898 the Kauri Gum Industry Act was brought into law, another act of environmentalisation that prevented anyone other than British subjects from engaging in the trade.

Northwood’s father worked as an industrial pharmacist and, in its early stages, photography grew naturally out of this line of work. Barthes wrote in Camera Lucida that photography’s invention should be credited not to painters, opticians or lens grinders but to the chemists who produced the solution for fixing the image. Climate scientists in Britain have been studying the rings of the ancient swamp kauri for data on the fluctuations in atmospheric carbon; data that can be useful for understanding and combating our own period of climate change. The logs are preserved in a kind of chemical bath of dead but undecayed organic matter. Has not the photograph often been thought of as the preserved uncanny presence of the past, and cared for accordingly? Photography is also the eye of modernity. As much as the melting heat of capitalist exchange can reduce any solid object to units, shifted across the territories of the globe, the photographic image too peels the skin of the earth away, and with ever intensifying velocity, is sent around the world. Nadia Bozak suggests that industrial imagery produced by photography, cinema, video and digital technology form “the hydrocarbon imagination5 ; images for the age of industrial and electronic subordination of nature. Yet, Andre Bazin in a famous text wrote that “[p]hotography affects us like a phenomenon in nature, like a flower or snowflake whose vegetable or earthly origins are an inseparable part of their beauty.”6

Nugget of kauri gum. Northwood brothers :Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-011212-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22648849. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Kauri tree, Northland. Northwood brothers :Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006247-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand.http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23213108. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Man standing beside a kauri log, Herekino, Northland. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-004888-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22892421. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Northland bush scene, with kauri logs ready for transportation. Northwood album 4. Ref: PA1-q-180-044. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22766935. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Northwood, Arthur James, 1880-1949. Bullock team hauling logs through the bush. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006336-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22748240. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Northwood, Arthur James, 1880-1949. Digging for gum, Northland. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-011220-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22785375. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Māori digging kauri gum. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-004939-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22682639. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

![Gum diggers pumping water out of gum hole [ca.1910]. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006274-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22728446. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.](/media/cache/d3/b4/d3b4df1a9c8f8f3d9f051cfc375d2f82.jpg)

Gum diggers pumping water out of gum hole [ca.1910]. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006274-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22728446. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

![Woman with shovel and gum spear [1914]. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/2-042675-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22310676. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.](/media/cache/25/1d/251d0f9f893fd9e62f36ed6dbf9f6a6f.jpg)

Woman with shovel and gum spear [1914]. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/2-042675-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22310676. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Man digging for gum. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/2-029857-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22839789. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

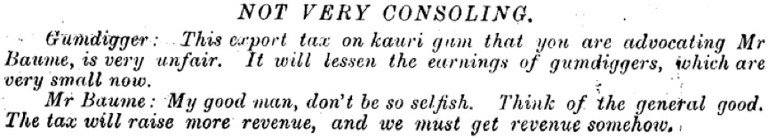

Untitled Illustration. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/6494282. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image

Sorting kauri gum at Michelson and Company, Auckland. Making New Zealand: Negatives and prints from the Making New Zealand Centennial collection. Ref: MNZ-0707-1/4-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23214653. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

![Gum diggers. Northwood brothers [ca.1910]: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-011208-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22901771. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.](/media/cache/d7/6e/d76e8ebe4fd5380aef6ee8af8fb73a41.jpg)

Gum diggers. Northwood brothers [ca.1910]: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-011208-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22901771. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Gum diggers playing cards in camp. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-011230-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23226852. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Group watching a boxing match on a gum field. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-011205-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22795592. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

Boy seated by a large nugget of Kauri gum. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/2-051968-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22334258. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

![Marjory Smith with a large piece of kauri gum, Northland [ca.1917]. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006276-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23109618. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.](/media/cache/a4/3f/a43f0a4167b09331b22095ff526227e8.jpg)

Marjory Smith with a large piece of kauri gum, Northland [ca.1917]. Northwood brothers: Photographs of Northland. Ref: 1/1-006276-G. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/23109618. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

W. B. Stevens, Photo. An Evening Pastime — Kauri Gum Carvings. New Zealand Illustrated Magazine, 01 February 1902. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/2707130.

Collection of kauri gum samples exhibited by J H McCarroll - Photograph taken by Leslie Hinge. Panama-Pacific International Exposition album 1. Ref: PA1-o-402-33. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. http://natlib.govt.nz/records/22827228. Permission of the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, must be obtained before any reuse of this image.

About the author

Richard Shepherd is an artist and writer living in Wellington, New Zealand.

-

1.

Sean Cubitt, “Angelic Ecologies,” Millennium Film Journal (2013) http://www.readperiodicals.com/201310/3157631091.html

-

2.

Paul Moon, Encounters: The Creation of New Zealand (Penguin Books, 2013), 147-158.

-

3.

Ibid. p.151

-

4.

Ibid. p.155

-

5.

Nadia Bozak, The Cinematic Footprint: Lights, camera, natural resources, (New Brunswick:Rutgers University Press, 2011).

-

6.

Andre Bazin, “The Ontology of the Photographic Image,” Film Quarterly, 13(4) (1960).