Exhibition Essays

Enjoy Gallery Catalogue 2006

December 2006

-

Dear Reader,

Paula Booker -

Good Willing

Eve Armstrong, Rachel O’Neill -

Rhythm is best considered fractally...

Pippin Barr -

The Lucky Sod

Melanie Oliver -

Treading the Boards

Andrea Bell -

Old Money

Jessica Reid -

Sex and Agriculture

Jessica Reid -

Mowing down the puppies, and other suburban stories

Sandy Gibbs -

Call & Response

Louise Menzies -

The Reconstruction and Retrieval of Enjoy Public Art Gallery

Michael Havell -

Becoming Animal: Essays on Aura 2006

Anna Sanderson -

Looking Up

Louise Menzies -

Powder Pink and Sky Blue Dreamland

Rob Garrett -

Action Buckets

Melanie Oliver -

Whose Street is it Anyway?

Melanie Oliver -

Can you hold the line please?

Melanie Oliver -

Ghetto Gospel

Thomasin Sleigh -

Hot Air

Paula Booker -

Statement

Kaleb Bennett -

Amigos

Paula Booker -

S.O.S. Save Us From Ourselves

Mark Williams -

Time warp

Thomasin Sleigh -

Every Now, & Then

Amy Howden-Chapman

Amigos

Paula Booker

In late 2006, New Zealand expat artist Fiona Jack brought together a group of Los Angeles-based artists for a curated group exhibition: Royal Alumni. A dislocation of context and relationships occurred when a small selection of artists from another part of the world assembled for a Wellington exhibition, allowing the visual arts community here to see how another community presents itself.

An earlier version of the exhibition’s title is telling: Mis Amigos de LA. The show is premised upon a group of friends bringing their work together, as its curator Fiona Jack explains: “It’s pretty much people I like who make work I like, all CalArts people.” Beyond this, a loose thematic thread also draws these works together—many of the artists engage with the notion of spectacle as it pertains to the LA context.

Upon entering the gallery, visitors were met by a conversational but sparse arrangement of mainly singular works by each artist, including large drawings on paper, unframed photographs, a collection of small sky-blue flags, a slide and an audio installation. Happily, the display and scale of the works belied their arrival by airmail.

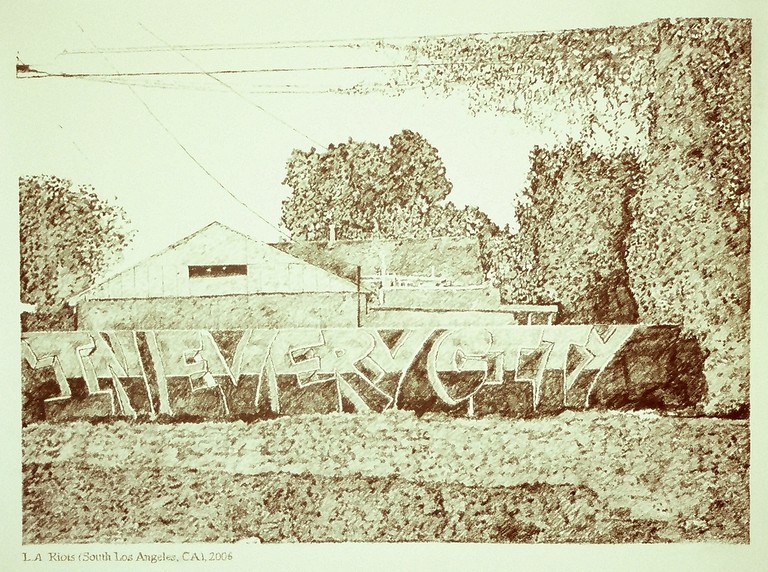

Josh Stone’s large sketches rendered the details of streets, traffic signs and suburban shrubbery and created a sense of another place. His drawings seem to disrupt the cultural and spatial stereotyping of the Los Angeles area’s history. Stone, an artist and DJ, employs his Jewish-American perspective to rethink aspects of LA folklore.

Also reflecting on historical folklore, Nate Harrison used musicology to uncover issues relating to copyright and information sharing. His work for Royal Alumni was an audio installation titled Can I Get An Amen? Harrison’s work unfolded a critical and historical perspective, delving into the history and subsequent use of what the artist claims is the most sampled drumbeat in the history of recorded music—the Amen Break. A deeply intoned and monotonous narration by the artist discussed this six-second drum loop, which originated from a 1969 soul track by The Winstons called Amen Brother.

Harrison’s work scrutinizes the techno-utopian notion that “information wants to be free” and highlights the Amen Break’s peculiar relationship to current copyright law.1 First sampled in the late Eighties by hip hoppers NWA, the break has since been chopped up and re-configured to create the majority of rhythms used in all ragga and breakbeat music produced around the world in the last ten years. Harrison presented his work as an acetate record, a dubplate. The dubplate is an affordable pressing technique for limited runs—artists’ pressings for example—however the heavyweight vinyl degrades with each play, rendering the disc unplayable after about fifty uses. While the installation set-up was similar to a listening post in a record shop, the work’s banal, informational qualities, combined with its temporal fragility, made it a strangely compelling piece.

A large colour photograph by Rebecca Hobbs was mounted unframed on the wall and injected some South Pacific imagery into the exhibition—the image showed a single Nikau palm on a steep, grass slope, being scaled by a small figure. Working with a stuntman, Hobbs created a series of photos that are surprising and unnerving.

Fiona Jack’s own artwork for the exhibition, 75 Cuban Revolutions, is the second part of a project developed for a show in Havana in 2006, about the illegal Cuban libraries that loan out banned books. Her wall of sky-blue flags was a melancholic homage to the strength of the heroes of Cuba’s resistance. They flapped quietly and flaccidly, each of the 75 flags bearing the Christian name of a librarian in memorial: Arturo, Juan, Maria, Lazaro ...

Also featured was George Kontos, a Greek artist now based in Los Angeles, whose earlier career as an architect and VJ has helped shape a fascinating practice of cultural and architectural critique.

The author of the ongoing Living History Project, which questions the construction of history, artist Kim Schoen is also no stranger to historical precedents. Schoen invited a group of people to photograph a fireworks display held over a dry lakebed in the Mojave Desert in Southern California. She then collected and edited their images into an ambiguous collection depicting explosions suspended against a blue sky.

Recent public debates and publications such as Jens Hoffman’s The Next Documenta Should be Curated by an Artist have called into question the relationship between artists and curators.2 Exhibitions like Royal Alumni add to this dialogue in a small way, bringing to our attention the multifarious works of “etc.-artists”. These are the artists—according to The Next Documenta’ contributor Ricardo Basbaum—who do not fit easily into categories, who question the role of the artist.

“When an artist is a full-time artist, we should call her/him an “artist-artist”, when the artist questions the nature and function of her/his role, we should write “etc.-artist” (so we can imagine several categories: curator-artist, writer-artist, activist-artist, producer-artist, agent-artist, theoretician-artist, therapist-artist, teacher-artist, chemist-artist)”.3

I think the value of The Next Documenta Should be Curated by an Artist is in its questioning of power structures and discussions about the changing roles of the artist and the role of curator as auteur, which has developed in past decades. The inherent value in the exhibition Royal Alumni, however, is the way it brought to light nuggets of artistic production in small creative communities that may otherwise be difficult to unearth by an institutional curator. Fiona Jack would probably be happier in the artist-artist role, but with a little coaxing, she became a curator-artist, bringing together architect- artist, DJ-artist, activist-artist and more. Her access to and friendship with these artists enabled an Enjoy audience to see newly produced work from a community like their own: work that is centered on a particular location and hinged on personal relationships. Although Royal Alumni was not an explicit meditation of the place of the artist in contemporary practice, such debates indeed sit effectively against Jack’s warm depiction of an art community.

-

1.

This phrase became a motto for the free content movement, a group responsible for creating a shift towards liberalisation of information ownership and copyrighting. The quote “Information wants to be free” is originally attributed to Stewart Brand, delivered during his speech at the inaugural Hackers Conference in 1984. Brand is cited here: http://www.anu.edu.au/people/Roger. Clarke/II/IWtbF.html (Retrieved October 2007).

-

2.

Hoffman asked: What happens if artists take over and occupy the territory that is usually reserved for curators? He asked artists to propose a concept for a large-scale group exhibition such as Documenta. This turned up varied types of responses—from proposals for the curated project to a rejection of the mantle of curator and all it connotes.

Jens Hoffmann, Cur. The Next Documenta Should Be Curated by an Artist (New York: e-flux, 2003).

-

3.

Ricardo Basbaum,“Documenta, I love etc. - artists” in Jens Hoffmann, Cur. The Next Documenta Should Be Curated by an Artist (New York: e-flux, 2003),14.